Gold’s strong performance over the last two years must be seen as an acceleration in the deleveraging of the global financial system. After many decades of inordinate credit creation—leading to excessive debt levels, asset bubbles, and too much monetary interdependence between nations—the financial system has started to heal itself through a rising price of gold.

The gold price will continue to rise in the years ahead until stability is restored.

Increased trust in credit instruments since the Second World War has inflated the global financial system to startling proportions. Rising geopolitical tensions, debt overhang, and inflation are now undermining this trust, leading to a new balance between financial instruments with counterparty risk (credit) and without counterparty risk (gold) in favor of the price of gold (deleverage).

Before we dive into the data that shows the price of gold can easily double in the coming years, let’s begin with some theory.

The Hierarchy of Financial Instruments

Simplified, the economy can be divided into the financial system—consisting of financial instruments such as money, stocks, bonds, and derivatives—and goods and services.

What distinguishes financial instruments from goods and services is that the former have no “use-value” to us humans. We can wear a sweater, eat a sandwich, ride a bicycle, and hire a contractor to paint our houses. That’s why goods and services are often referred to as the real economy.

Financial instruments are a means to an end. Because of their intermediary role, the value of financial instruments depends on trust. We accept money for the work we do because we trust we can use it the next day to buy bread at the bakery. People invest in stocks because they trust the economy will grow and companies can increase profits. And so forth.

However, not all financial instruments are created equal. There is one asset that has zero counterparty risk because it’s not man-made: gold. All other financial assets are a form of credit but differ in degree of creditworthiness. These differences make up the hierarchy of financial instruments.

Exter’s inverse pyramid is an excellent framework to capture the hierarchy of financial assets and model the financial system, with the aim of understanding debt cycles. By extension, the model works as a long-term gold price indicator, as the price of gold commonly rises at the end of a debt cycle.

Graph 1. My version of Exter’s inverse pyramid1. The pyramid’s horizontal axis is about quantity and leverage. Its vertical axis is about quality and trust. Note that in moderation there is nothing wrong with credit, but too much of it will choke off the economy, and too little means foregone opportunities.

At the bottom of the pyramid sits gold, which is scarce, universally accepted, and has no counterparty risk because it’s no one’s liability. Trust in gold is rock solid because it has an unbeatable 5,000-year track record as a store of value.

Above gold in the pyramid is the national currency, which is a form of credit as it’s a liability of a bank2. Credit requires more trust to function than gold, and the higher up the pyramid the riskier the credit instrument. Following national currency are debt securities, equity, and finally derivatives.

Gold is at the bottom of the pyramid and ultimately backs all forms of credit resting on top of it. Hence, virtually all central banks own gold.

Debt Cycles and the Gold Price

In an economic boom, trust in credit instruments increases and assets and liabilities in the financial system are expanded (credit is created). At this stage of the debt cycle, the crown of the pyramid widens: debt levels and leverage go up.

Eventually bubbles in credit assets develop, which can be visualized as a huge crown weighing on a tiny foot of gold. The financial system becomes unhinged.

During the inevitable recession, defaults cause balance sheets to contract, trust in credit instruments to flop and investors running down the pyramid to gold. As the gold price rises the stand of the pyramid enlarges, adding more trust and stability to the financial system. Rot is making a place for healing.

The shape of the pyramid is remodeled until stability is reached—a solid balance between gold and credit. While the overall size of the pyramid grows over time, its shape morphs simultaneously with debt cycles.

From Perry Mehrling, Professor of International Political Economy and intellectual mentor of Zoltan Pozsar (2013):

In a boom, the credit begins to look like money. … Forms of credit become much more liquid, they become much more usable to make payments with. And in contraction, you find out that what you have is not money, it’s credit actually. In a contraction, you find out that gold and currency are not the same things. That gold is better. …

So there is a loss of qualitative distinction between money and credit in the expansion, and then a reassertion of that distinction.

More succinct, from J.P. Morgan’s testimony before Congress in 1912 (page 5):

Money is gold, and nothing else.

Gold Will Continue to March Higher

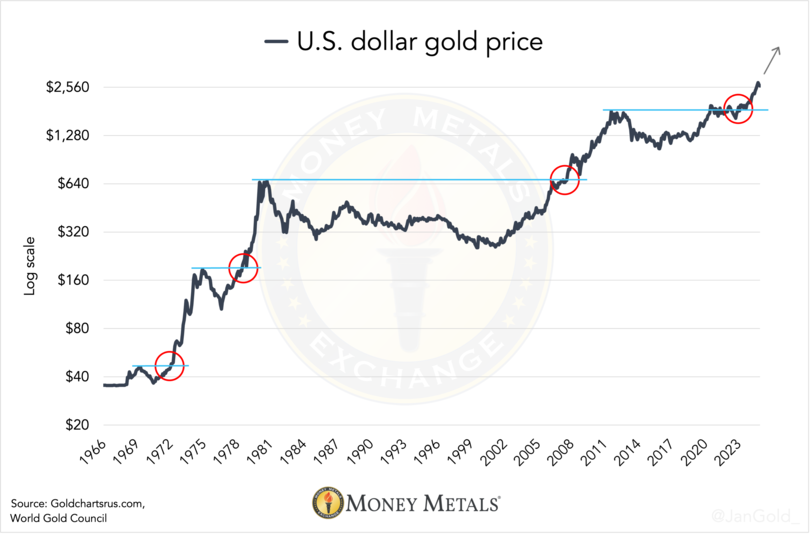

The price of gold increases sharply at the end of a debt cycle. One way of visualizing debt cycles is charting ratios between the value of gold and credit assets. Such charts offer clarity of where we are in the cycle and what’s next for gold.

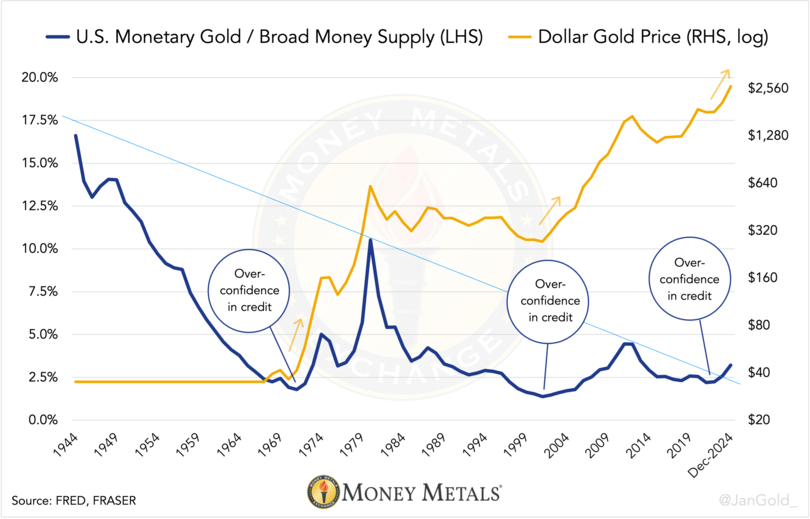

As an introduction, chart 1 below shows the ratio between the value of U.S. monetary gold and the broad money supply (M2). After the Second World War, every time this ratio fell below 2.5% (overconfidence in credit), a gold bull market followed.

Chart 1. Technically, the gold-to-fiat ratio has “broken out.”

The last time the U.S. gold-to-broad-money ratio dipped below 2.5% was in 2022, and gold has been going up strongly since.

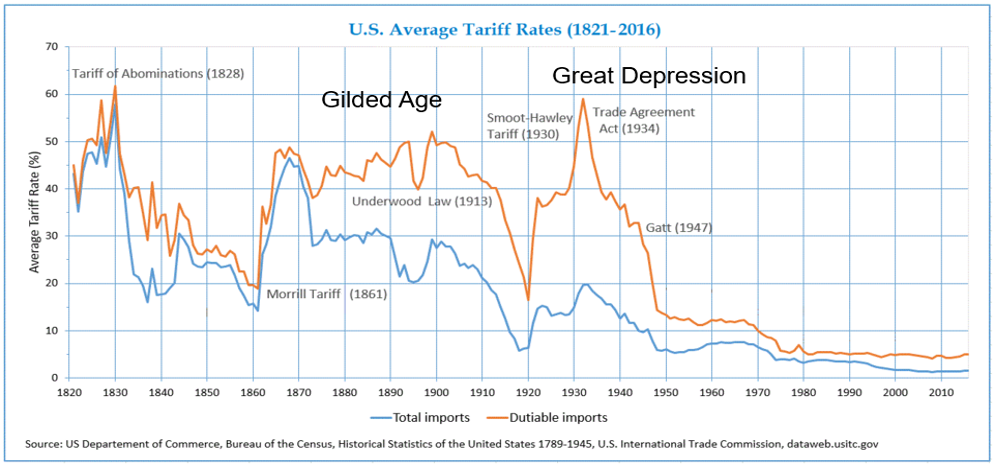

The war in Ukraine that started in early 2022, made the West freeze Russia’s dollar and euro assets, which triggered the deleveraging of the global financial system. Central banks are buying gold hand over fist, racing down Exter’s pyramid, causing the gold price to skyrocket.

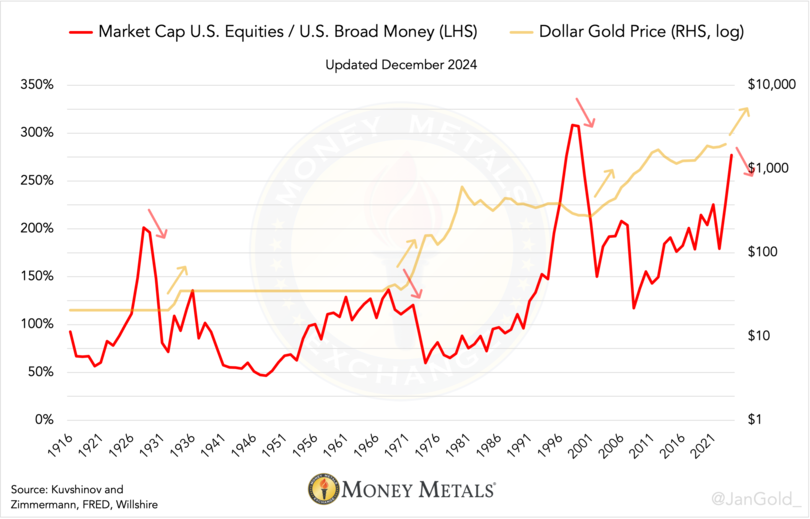

Another angle to track debt cycles is to make use of ratios between two types of credit. Chart 2 shows the ratio between the total U.S. equity market cap and broad money supply. Evidently, every time since the 1920s when equities fall relative to a national currency, gold goes up.

Chart 2. During the first crash in stocks, the U.S. was still on the gold standard. To stem the crisis (Great Depression) the U.S. government decided to devalue the dollar against gold—the gold price went up. Of interest, this chart looks eerily similar to the Shiller S&P500 PE ratio.

The chart indicates that the equity-to-fiat ratio is nearly at a record high now, so gold is more likely to perform well in the near future than to reverse course.

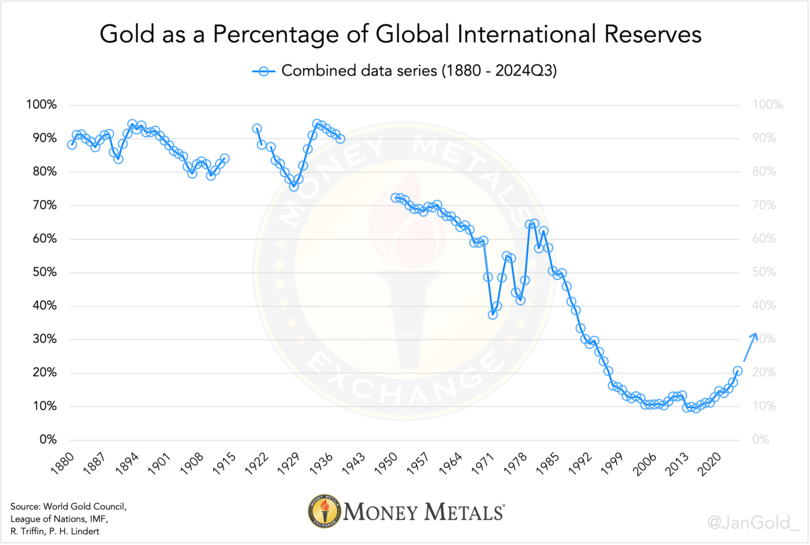

On a global level, countries officially agreed they could hold foreign currencies, and financial assets denominated in foreign currencies, as a substitute for gold reserves to back their monetary base at the Genoa conference in 1922. Foreign exchange holdings took off after the Second World War when central banks commenced accumulating more and more dollars.

An important gold-credit ratio thus to analyze is gold’s share of global international reserves (foreign exchange and gold). My data goes back to 1880.

Chart 3. Estimates are based on data from the IMF, World Gold Council, Peter H. Lindert, Robert Triffin, and the League of Nations.

Until ten years ago, the expansion of foreign credit on central bank balance sheets significantly increased leverage within the international monetary system, from a gold-to-total-reserves ratio of 95% in 1933 to less than 10% in 2015.

Current geopolitical tensions, weaponization of the dollar, and mounting concern regarding the sustainability of the U.S. public debt (122% of GDP and rising) are deleveraging the global financial order.

Gold’s share of total reserves is sharply going up. According to my estimates—that include unreported purchases by central banks—gold’s percentage of total reserves reached 21% in Q3 of 2024.

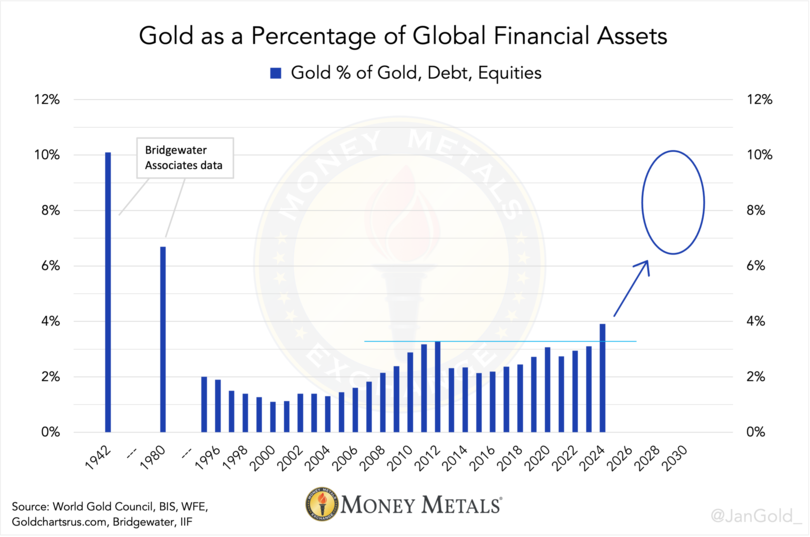

In a perfect world, we would have at our disposal data of all financial instruments going back to 1800. Unfortunately, these numbers aren’t publicly available, but I did find estimates by Bridgewater on the ratio between all above-ground gold and financial assets (in this case gold, debt, and equity) from 1924 until 2020. I was able to mimic Bridgewater’s methodology for the last two decades and extend their series.

Chart 4. Data until Q3 2024. Gold’s share of financial assets peaked in 1942 at 10%, and in 1980 at nearly 7%. These peaks roughly coincided with the start of new debt cycles.

We can see in the chart that gold has broken out relative to credit assets, which will attract more investors to gold. (In 2024, the S&P 500 went up by 23%, long-term Treasury bonds went down by 8.06%, and the dollar gold price increased by 26%.)

Gold to $8,000 per Ounce?

We don’t need to discuss much more for an assessment of what’s in store for gold. Equipped with a correct understanding of the financial system, awareness of where we are in the debt cycle, and evidence of a turnaround in markets, we have a worthy indication.

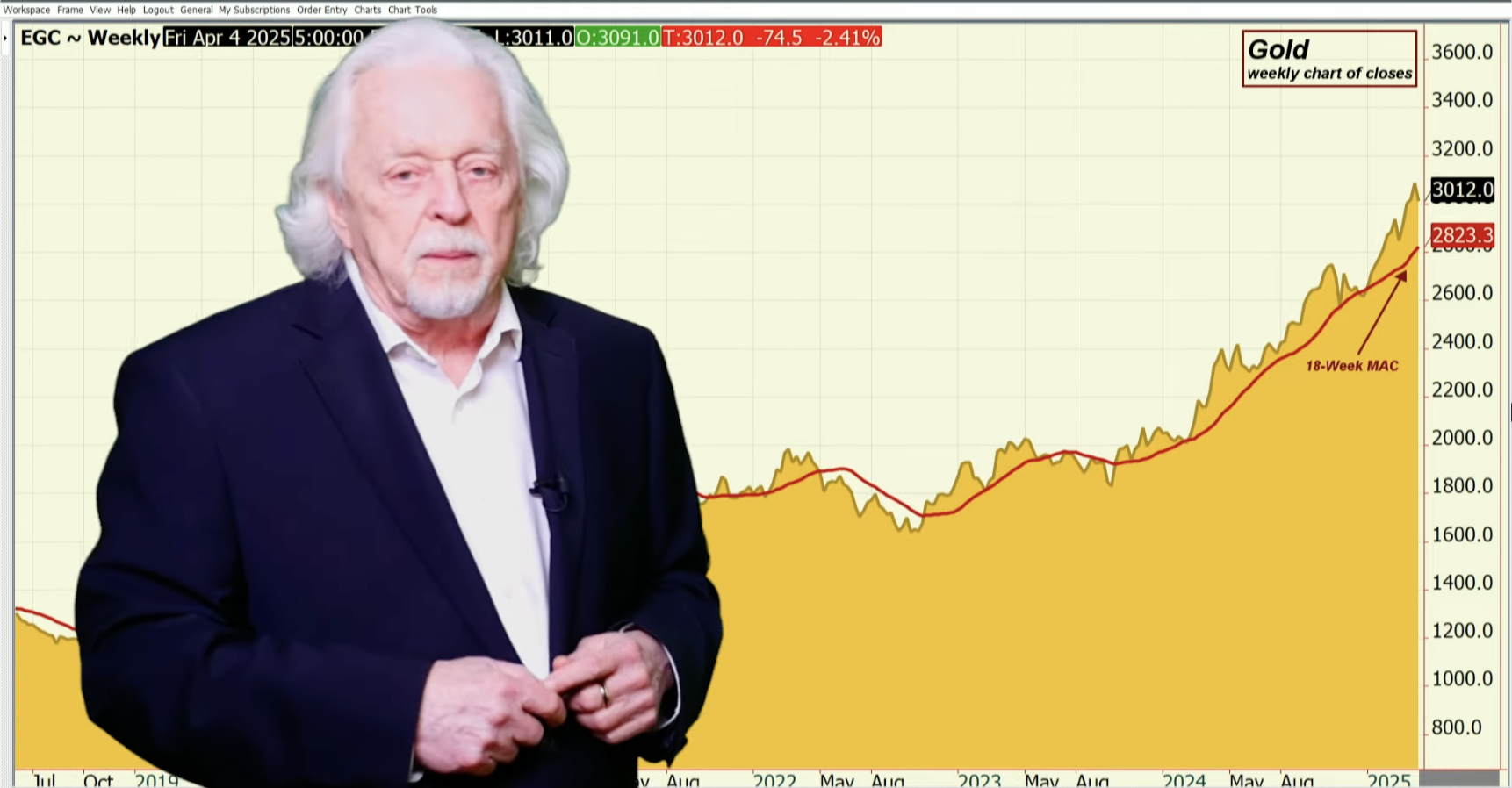

The charts point out we are at the end of a debt cycle. Regarding the turnaround in markets, the raging wars emphasize counterparty risk in the system, central banks are buying heaps of gold, gold-credit ratios have broken out (charts 1 and 4), and, last but not least, the gold price is rising fast.

Chart 5. From a technical perspective, the gold price in dollars has broken out and can multiply from here as it has done in the past after breakouts.

Based on the data from the charts, I expect the price of gold to complete this bull market until it reaches $8,000 an ounce, give or take, and reset the pyramid—which would be only natural.

Watch this space, and the Money Metals X-account, as I will keep tracking gold versus leverage in the financial system and update the charts on a monthly basis.

Notes

- The same sequence in assets can be found in the IMF’s Balance of Payments Manual 6 on pages 20-28, 84, 100, 112, 290, and 307.

- For the sake of simplicity, there is no distinction made between national currency issued by central banks and commercial banks in this article.

- Regarding the model described above it is not needed to tell apart periods with or without a gold standard. After all, national currency can be devalued against gold during a gold standard and the peg can be abandoned altogether.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply