In my last Deeper Dive, I repeated my position that I’m not concerned about BRICS creating a new currency that cuts into the dollar as the global trade currency. In case you thought that meant I think the dollar stands secure, let me highlight that I also said the dollar will still die its own death due to its own mismanagement. Now, I want to talk about what that means.

If I should prove right that another currency does not gain enough respect to replace the dollar, how will the dollar die? To explain that I need only point out one simple fact. The world traded and had foreign exchange without dollars for centuries before the dollar was invented. It managed to do so without the pound as a global currency and without francs as a global currency. The world doesn’t need a global fiat currency or even a metals-backed global currency in order to trade or even exchange money.

You see, while it is very cumbersome for individual citizens to trade with each other in daily business using silver and gold due to trust factors and many other things, it is quite easy for central banks to do it on behalf of their citizens. A central bank can take a foreign currency collected by a business that uses that central bank’s own local currency and give the business the appropriate amount of local currency in exchange. So long as it has a working relationship with the central bank that creates the traded foreign currency, it can from time to time reconcile accounts by returning the foreign currency to the central bank of its origin in exchange for gold. Then it can use that gold when other central banks have a load of the local currency to exchange with it.

Often, the gold is not even physically moved. So long as the central banks can trust each other, they merely earmark a certain amount of the gold they hold as being owned by the other central bank making the exchange. Whenever they want, of course, the central banks can physically move the gold from one nation to another. It was done that way for centuries and, thus, some gold also sank to the bottom of the sea. It’s also a system with notorious robbery risks, but it has been used a lot over the centuries.

By this simple, old-fashioned mechanism, the BRICS nations that we talked about last week can exchange their own local currencies with each other and leave the dollar out as often as they want without creating a currency that competes on a global stage. All they need is an agreement for exchanging gold because not all central banks want more and more gold or want to make exchanges that way, but most are still used to doing some exchanges using physical gold, and it’s coming back in style even with CBs.

According to the Atlantic Council,

Over the past twenty-three years, the US dollar (USD) has declined gradually as a share of global foreign exchange reserves, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The shift has not benefited any other major currency viewed as a potential competitor to the USD, like the Euro, the Great British pound (GBP), or the yen. It has instead favored a group of lesser-used currencies, including the Canadian dollar, the Australian dollar, the Renminbi, the South Korean won, the Singaporean dollar, and the Nordic currencies. If gold—which has recently experienced a surge in purchases by many central banks, as well as the general public—is included in reserve asset portfolios, the share of the USD is smaller than what the IMF has highlighted. As geopolitical confrontations deepen, the share of the USD in global reserves is likely to continue declining in the future, eventually diminishing the dominant role of the dollar and the US in the international financial system. (“Going for gold: Does the dollar’s declining share in global reserves matter?”)

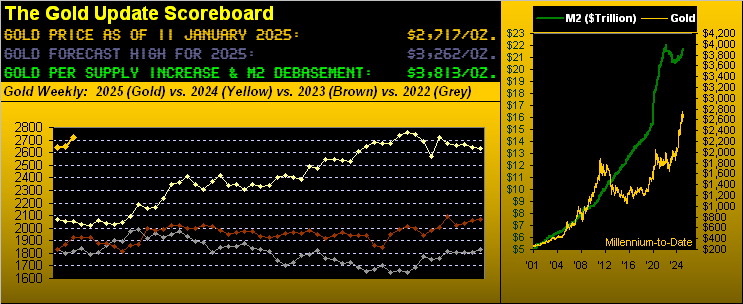

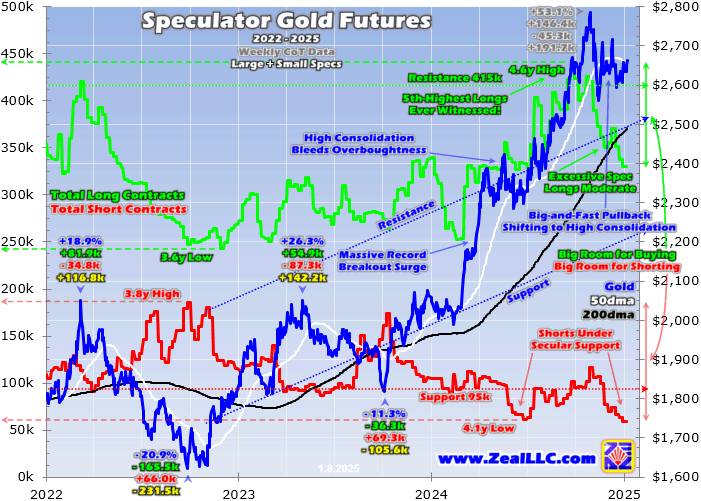

So, the diminishment of the dollar is in process and has been going on for a long time. It isn’t going much faster now, and will almost certainly continue apace. That is the move we see happening. Very small currencies have benefited only because they are so small in concern that it doesn’t take much to move the needle. The dollar’s big slide in foreign exchange, however, is toward gold—particularly of late. Central banks have started hoarding it again, particularly in the BRICS nations.

They don’t need a currency backed by gold to use their gold for foreign exchange. They can already move gold all day long, but they need enough to handle the volume, and one country can experience a pile-up in gold that is expensive to guard as another experiences a shortage so it is not a trouble-free system, but neither is a global currency as we saw when effectively a pile-up happened between European countries where keeping the euro in stable and place caused harder strains on some smaller economies than on larger ones.

That is why we see the following kinds of moves in foreign exchange and gold:

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, the world’s central banks have increased their gold purchases in an attempt to manage heightened financial system uncertainty. Doing so has pushed gold prices up by 138 percent over the past sixteen years to reach the current record highs of over $2,600 per ounce. Gold buying has accelerated further in recent years as part of a growing popular demand. In 2022 and 2023, central banks purchased more than one thousand tons of gold per year, more than doubling the annual volume of the previous ten years. Purchases have been spearheaded by the central banks of China and Russia, followed by several emerging market countries including Turkey, India, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Thailand. In particular, the People’s Bank of China has raised the share of gold in its reserves from 1.8 percent in 2015 to a record 4.9 percent at present. At the same time, it has cut its holding of US Treasuries from $1.3 trillion in the early 2010s to $780 billion in June 2024.

The fact is that the Fed’s mismanagement of the dollar, which created a huge real-estate bubble that imploded from 2007-2010, resulted in a lot of distrust in the Fed, and, so, banks began to diversify more into gold at that time. The weaponization of the Fed’s dollar by the US government has also created huge distrust in the limited number of nations that got hit with sanctions. The worst distrust, however, has come since the Fed started tightening the dollar, which has done huge damage to other economies and central banks. Even that has only wiggled the trajectory of the dollar downward slightly steeper than the path it has been on for decades as shown in this long-term graph (following which I’ll lay out the deeper details diminishing the dollar’s dominance)…

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply