For the survival medic caring for their family or a group off the grid, most patient encounters will be unhurried, routine, and one-on-one. If you are trained and accumulated the right supplies, your encounter with any one patient should be, with any luck, well within the limits of your expertise and resources.

But the aftermath of a major disaster may take the family caregiver to the brink with regards to their family’s survival. In the New Normal, the medic might be confronted with multiple victims of trauma simultaneously and have to make quick decisions. We refer to this type of event as a mass casualty incident (MCI), although more recently, some professionals have taken to the term MASCAL.

A mass casualty incident is any event in which your medical resources are inadequate for the number and severity of injuries incurred. MCIs can be quite variable in their presentation and occur in both good times and bad. They might be:

- Terrorist bombings (Boston marathon).

- Active shooter events (Las Vegas Mandalay Bay)

- The aftermath of a storm, such as a tornado or hurricane (Helene, Katrina).

- Consequences of civil unrest (too numerous to count).

- Mass transit mishaps (train derailments like East Palestine, Ohio, plane crashes like 9/11).

- Doomsday scenario events, such as nuclear weapon detonations (Hiroshima, ?Ukraine?).

The above would be major events covered nationally by the press, but an MCI could be as simple as a multiple-car accident with three casualties in a two-ambulance town.

You might even consider the COVID-19 pandemic an MCI. From an organizational standpoint, it was. As medical resources were overwhelmed in some areas, similae command structures and community safeguards were implemented in an attempt to limit the number of cases and stay within the available resources of personnel and equipment.

Pandemics come with their own unique problems: In a car accident or tornado, the rescue personnel arrive after the event and rarely become victims themselves. With infectious disease outbreaks like the Ebola epidemic of 2014, however, the medical assets themselves started getting sick in large numbers, leaving less resources for patient care.

Pandemics aside, we are talking here about incidents where there are multiple traumatic injuries. The response to injuries caused by a tornado or active shooter is different than the response to a pandemic. These events are difficult to predict and the damage is done in a matter of a few minutes. A multiple vehicle or mass transit accident occurs in a second. In these situations, all the emergency resources of the city or town must go activate immediately.

The effective medical management of the above events requires rapid and accurate triage. Triage comes from the French word “trier” (to sort). It’s the process by which medical personnel rapidly assess and prioritize injured individuals. When the first evaluations occur at the scene, it’s called “primary triage.”

In trauma MCIs, triage identifies those with injuries most likely to benefit from immediate, priority attention. In pandemics, triage identifies those who may require rapid isolation from the general patient population. In both cases, you attempt to do the most good for the most people. Note that I didn’t say: “the best possible care for each individual.”

The 5 “S’s” Of MCI Triage

As the first to arrive at the scene of an event with multiple casualties, you must assume to role of “Incident Commander” until someone with more medical expertise arrives. What do you do? Your initial actions comprise what we call the “5 S’s” of evaluating a mass casualty scene:

1)Safety Assessment: Many terrorists employ an insidious strategy using primary and secondary bombs. The main bomb causes the most casualties, and the second bomb is triggered as rescue personnel (you) arrive.

You might grimace when I advise not approaching the injured in a hostile setting. Yet, your primary goal as medic is your own self-preservation. Keeping the medical personnel alive is likely to save more lives down the road. You do your family and community a disservice by becoming the next casualty.

Here’s a tragic example: In the immediate aftermath of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, various medical personnel rushed in to aid the victims. One of them was a heroic 37-year-old Licensed Practical Nurse named Rebecca Anderson.As she entered the area, she was struck by a falling piece of concrete. She sustained a head injury and died five days later.

Another: Father Mychal Judge, a firehouse chaplain, rushed to the scene of the World Trade Center bombing on 9/11/2001, and provided support at the base of the North Tower. Father Judge was killed when the neighboring South Tower collapsed. So, whether it’s falling bricks or bullets flying, be as certain as possible that there is no ongoing threat.

2)Size up the Scene: Ask yourself the following questions: What’s the situation? Is this a mass transit crash? Did a building on fire collapse? Was there a shooting or explosion?

How many injuries are there? How severe are they? How many victims? Are there any uninjured that could assist you? Are the victims all together or spread out over a wide area? Are there lanes open that are large enough for vehicles to come through and help transport victims?

3)Send for Help: If you sized up the scene correctly, you have a lot of important information to pass on to emergency medical services or, in survival scenarios, other group members arriving at the scene.

If modern medical care is available, notify emergency services and say (for example): “I am calling to report an accident involving three cars at the intersection of Oak avenue and Elm street. There are at least seven people injured that require medical attention. Two persons are trapped in their cars and one vehicle is on fire.”

In three sentences, you have informed the authorities that a mass casualty event has occurred, what type of event it was, where it occurred, an approximate number of patients that need help, and the types of care or equipment that may be required.

In survival settings, use your communication device to notify base camp of the situation. Let them know what you’ll need in terms of personnel and supplies. If you are not medically trained, contact the person who is the group medic. The most experienced medical person who arrives at the scene becomes the new Incident Commander.

4)Set-Up: Determine likely areas for various triage levels (see below) to be further evaluated and treated. These are sometimes called “Casualty Collection Points” (CCPs). Also, determine the appropriate entry and exit points for victims that need immediate transport to medical facilities, if they exist. If you are blessed with lots of help at the scene, assign triage, treatment, and transport team duties.

5) S.T.A.R.T.: Triage uses the acronym S.T.A.R.T., which stands for Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment. The first round of triage, known as “primary triage,” should be fast (30 seconds per patient if possible) and does not involve extensive treatment of injuries. It should be focused on immediate life-saving interventions (LSIs) and identifying the triage level of each patient.

S.T.A.R.T.

Evaluation in primary triage consists mostly of quick evaluation of respirations (or the lack thereof), perfusion (adequacy of circulation), and mental status. Other than controlling massive bleeding and clearing airways, very little treatment is performed in primary triage. In an ongoing firefight, move live casualties to cover as soon as they’re identified.

Although there is no international standard, triage levels are usually determined by color:

- Immediate (Red tag):The victim needs immediate medical care and will not survive if not treated quickly (for example, a major hemorrhagic wound/internal bleeding). This person may die within minutes and has top priority for treatment.

- Delayed (Yellow tag):The victim needs medical care within several hours. Injuries may become life-threatening if ignored, but can wait until the red tags are treated. An example of a yellow tag would be an open fracture without major bleeding.

- Minimal (Green tag):Generally stable and ambulatory (“walking wounded”) but need some medical care (for example, broken fingers, facial burns, or a sprained ankle).

- Expectant (Black tag):The victim is either deceased or is not expected to live (for example, open fracture of skull with brain damage, multiple penetrating chest wounds).

Special cards are available for documenting evaluations of MCI victims. They look like this:

Some evolution has occurred since the START triage model was developed, leading to the SALT triage model:

A new system is being developed that will change this to ”Stable, Unstable, and Expectant” (deceased or beyond help). This MASCAL version isn’t very different from the current system, but adds treatment for fractures and other injuries that aren’t imminently lethal, such as fractures, at casualty collection points (CCPs). We’ll discuss this in future parts of this series.

Of course, the medic off the grid probably won’t have colored tags or tape. Instead, use felt markers (handy items to have in your pocket). If you only have a black marker, you can still write numbers on the victims’ foreheads. If you use numbers:

- 1 is immediate/red (top priority)

- 2 is delayed/yellow

- 3 is minimal/green

- 4 is dead/expectant/black

The number method is the standard in many countries. it’s also useful if you’re color blind.

Knowledge of this system allows a rescuer to understand the urgency of a patient’s condition. You should know that, without modern medical care, a lot of red tags and even some yellow tags will become black tags. It will be difficult, for example, to save someone bleeding internally without surgical intervention.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll discuss a simpler method for ongoing hostile settings proposed recently that is called “Move, Treat, and Transport.” We’ll also describe a possible MCI scenario, what goes into a true MASCAL kit, with perhaps some adjustments for long-term survival settings.

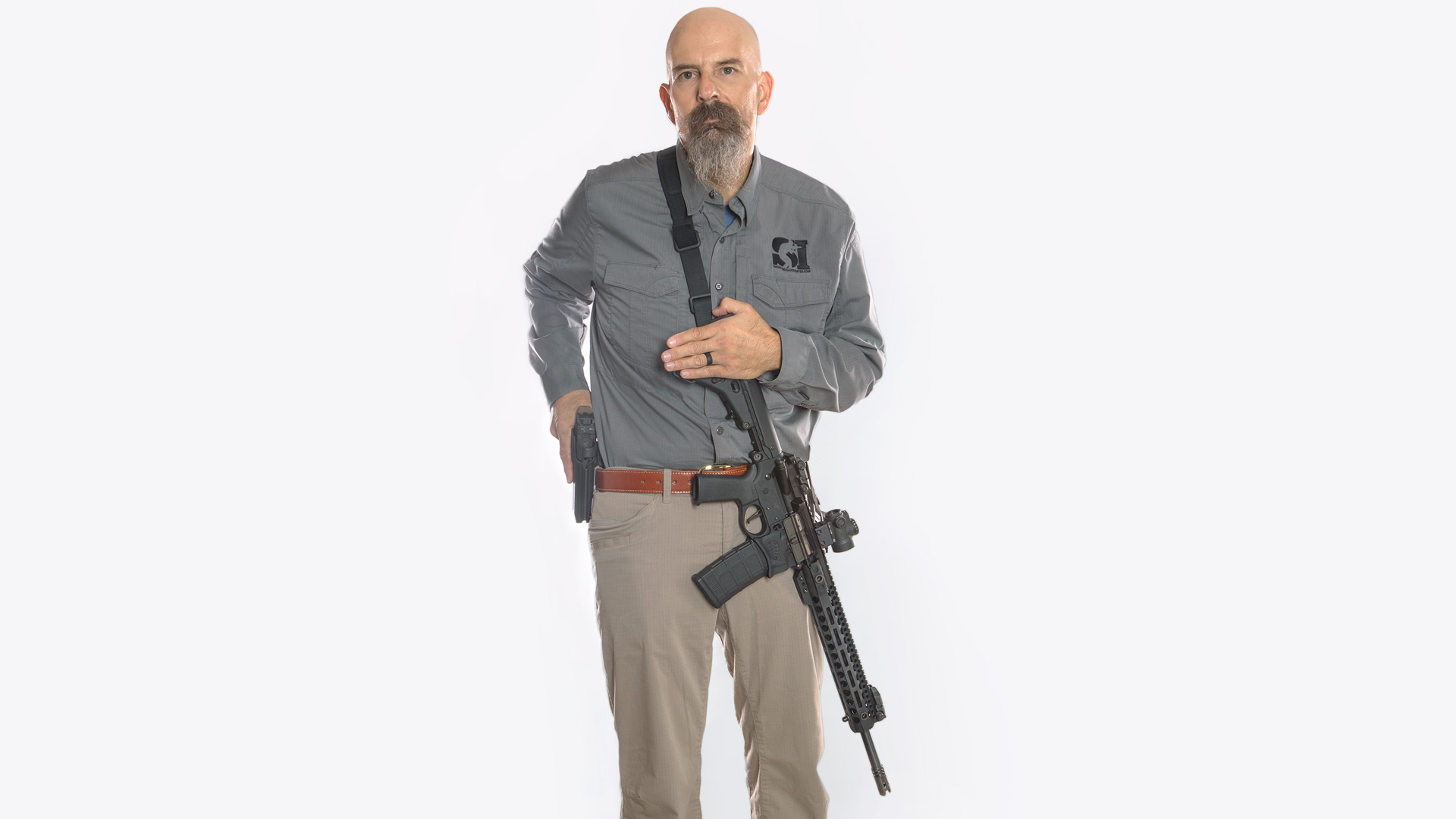

Joe Alton MD

Dr. Alton

Dr. Alton

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply