As the third most-consumed metal behind iron ore and aluminum, copper is all around us. Found naturally in the Earth’s crust, copper was the first metal used by humans, dating back to the 8th century BC.

Three thousand years later, homo sapiens figured out how to smelt copper from its ore, and to alloy it with tin to create bronze. Bronze was useful for tools and weapons, making it one of the most important inventions in the history of civilization.

The Copper Age

Nothing happens without copper; as it turns out, not even civilization itself. Beginning around 5,000 BC, the “Chalcolithic” (from the Greek “khalkos” for copper and “lithos” for stone) or Copper Age was a transitionary period between the Stone Age and the Bronze Age.

It was during this time that copper was introduced as a material that could be worked into metal, paving the way towards the use of bronze later on.

The archeological site of Belovode in present-day Serbia holds the distinction as the world’s oldest copper-smelting location, circa 5,000 BC. Copper was also found in the Near East beginning in the late 5th millennium BC. Later, pockets of copper technology began appearing in northern Italy and along the Mediterranean coast.

Copper was used to shape tools, weaponry, coins and jewelry.

The arrival of metal catapulted early Britain and other societies, including China, which has a long history of using metal objects, into a whole new chapter of civilization.

Copper minerals

According to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), an Australian government agency, there are around 160 naturally occurring copper-bearing minerals. Chalcopyrite, bornite, chalcocite, and native copper (an uncombined form of copper) are four minerals often mined for their copper content.

Chalcopyrite is the most abundant copper-rich mineral.

Azurite is a copper carbonate mineral that forms in the upper oxidized zones of copper ore deposits. It has a deep azure-blue color. When exposed to air and water, it often shows a rainbow-like iridescence. Since ancient times, it has been used as an ore of copper, a gemstone, and a pigment. Michelangelo and Leonardo DaVinci even used it to create blue hues in their paintings.

Malachite was one of the first ores used to produce copper metal. Often found with azurite, malachite is a mixture of copper, iron and oxygen. It has a deep green color that does not fade over time or when exposed to light. This made malachite a popular pigment for painting. Ancient Egyptians used it for tomb paintings. European painters, especially in the 15th and 16th centuries, loved the palette of greens it gave. Artists in India, Tibet, China, and Japan used it in murals, manuscripts, ceramics and lacquerware.

~ ‘Conducting change: Why copper is key to a renewable future’ by CSIRO, Oct. 27, 2023.

Uses

Sometimes referred to as “Dr. Copper” for its ability to diagnose the health of the global economy, copper is just as essential to modern society as to ancient civilizations — if not more so.

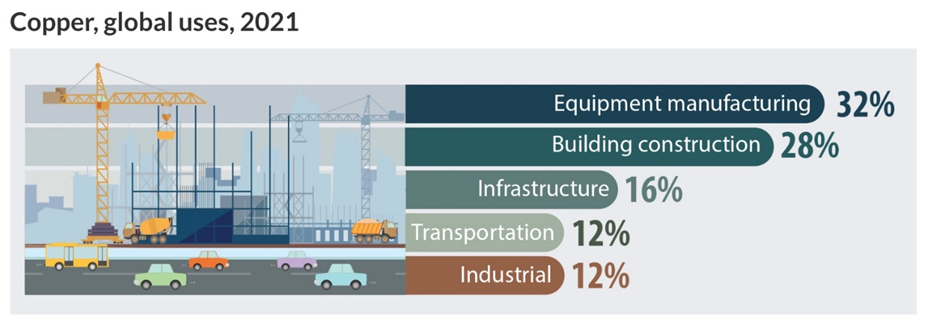

The Copper Development Association divides its uses into four categories: electrical, construction, transport and other. By far the largest sector for copper usage is electrical, at 65%, followed by construction at 25%.

Source: Natural Resources Canada

Copper is useful for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity. The only metal that has higher conductivity is silver, but silver is expensive by comparison.

Conductivity, combined with durability, malleability and dependability, make it ideal for wiring. Sprott notes that copper’s journey took a historic turn in the 1800s when its exceptional electrical conductivity sparked the revolutionary age of telegraphy and incandescent electric lamps to light homes.

Among electrical devices that use copper, are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves, and fire prevention sprinkler systems.

In telecommunications, copper is used in wiring for local area networks (LAN), modems and routers. The construction industry would not exist without copper; it is essential for wiring in residential and commercial construction. The red metal is also used for potable water and heating systems due to its ability to resist the growth of water-borne organisms, as well as its resistance to heat corrosion.

The transportation industry is reliant on copper for core components of airplanes, trains, cars, trucks and boats. A commercial airliner has up to 190 kilometers of copper wiring, while high-speed trains use up to 10 tonnes of copper per kilometer of track.

Automobiles have used copper and brass radiators and oil coolers since the 1970s. More recent applications include on-board navigation, anti-lock braking systems, heated seats, defrosting wires embedded in windows, hydraulic lines, and wiring for window and mirror controls.

Copper is a critical mineral for our infrastructure, including over 11 million km of electrical wires powering homes, businesses and industry in the United States alone.

The average home contains more than 90 kg of copper.

In 2022, the copper market was worth USD$183 billion, making it the third most valuable metals market behind only iron ore and gold.

Copper and electrification

Copper is the heartbeat of the global energy economy.

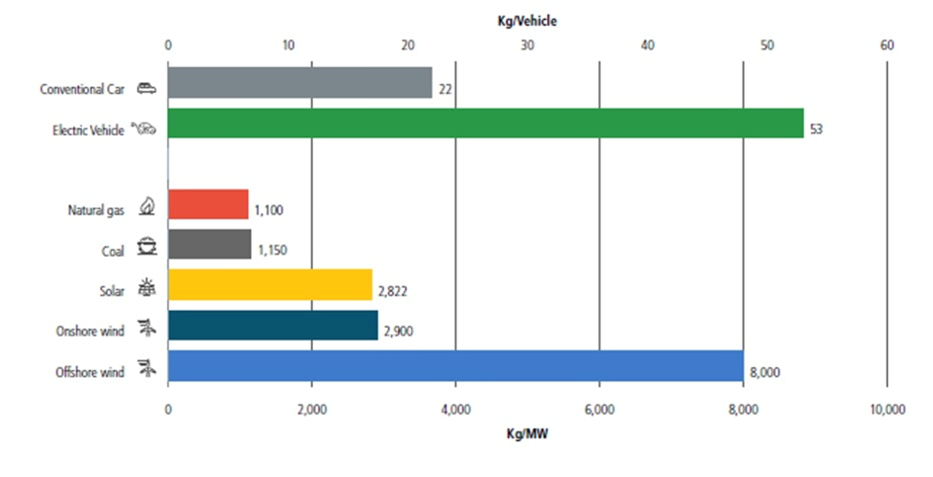

Millions of feet of copper wiring will be required for strengthening the world’s power grids, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes more are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. Renewable energies need five times more copper than non-renewables.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (NEF), clean energy currently consumes a quarter of copper demand, a figure that is projected to reach 61% by 2040, given our growing reliance on wind, solar and electric vehicles. (‘Copper: Wired for the Future’ by Sprott, Feb. 27, 2024)

Copper has been designated a critical mineral by several developed countries/ regions including Canada, the US, the European Union, China, Japan and India. Last year at the United Nations’ COP28 climate summit, 118 governments pledged to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030.

Copper’s role as a critical mineral led to its inclusion in over $30 billion of funding from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act.

The Sprott report says that, while copper is likely to take center stage as the leading electrification metal, existing copper supplies are dwindling and new mines take up to two decades to develop, which is creating a race to meet increasing copper demand.

Global investment in the energy transition reached $1.8 trillion in 2023; it now exceeds investments in fossil fuels. To reach “net zero” emissions targets by 2050, investments must average $4.8 trillion from 2024 to 2030 (that’s almost $5T every year for the next six years!). In the 2030s, the average annual investment would need to approach $7T.

Sprott makes the following points about copper demanded by electrification and decarbonization:

By 2050, it’s projected that the global electric grid will need to double in capacity to meet the 86% increase in electricity demand.

Shifting production to greener energy sources is expected to necessitate 427 million tonnes of copper by 2050. Last year, the mining industry only produced 22Mt.

The shift toward underground wiring, which requires twice as much metal as overhead lines, is intensifying the demand for copper.

Copper is essential in EVs, finding use in electric motors, batteries, inverters, wiring and charging stations. An EV requires 53 kilograms of copper in electric motors, batteries, inverters, wiring and charging stations, about 2.4 times more than a conventional combustion vehicle uses. This volume of wire can extend up to a mile in length. Although efforts are underway to reduce copper in EVs, demand is still projected to hit 2.8 million tonnes by 2030.

Renewable energy infrastructure, including solar and wind power, needs 2.5 to 7 times more copper than fossil fuel-based technologies, depending on whether the wind installations are onshore or offshore.

The role of critical minerals in energy transition. Source: IEA, May 2021

The role of critical minerals in energy transition. Source: IEA, May 2021

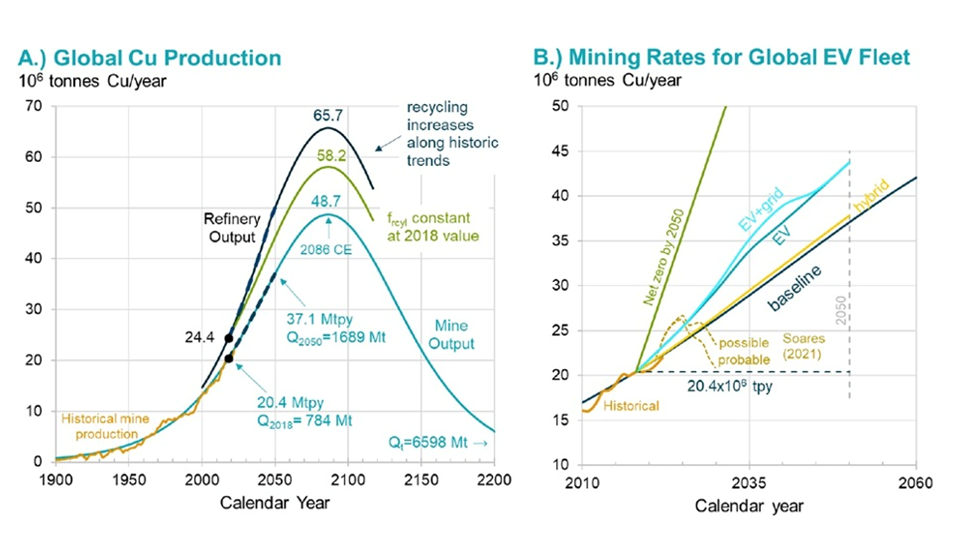

A new study suggests that electrifying the global vehicle fleet by 2050 will require an unrealistic ramp-up in copper production.

5 reasons we are entering the next copper super cycle

Researchers at the University of Michigan and Cornell University found that copper can’t be mined fast enough to keep up with current US policy guidelines to make the transition from fossil-fueled power and transportation to electric vehicles and renewable energies.

For example the Inflation Reduction Act calls for 100% of new cars to be electric vehicles by 2035.

“We show in the paper that the amount of copper needed is essentially impossible for mining companies to produce,” said Adam Simon, co-author of the paper, published by the International Energy Forum (IEF).

How impossible? The researchers found between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to mine 115% more copper than has been mined in all human history to 2018. This would meet our current copper needs and support the developing world without considering the green energy transition.

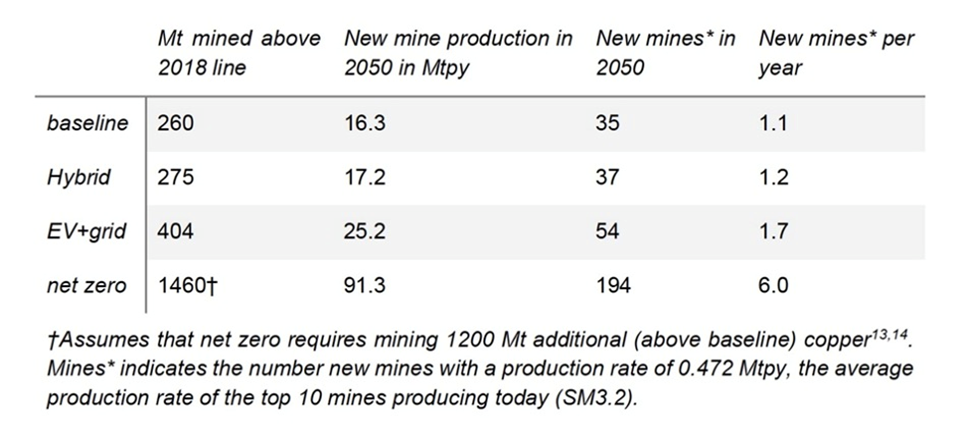

To electrify the global vehicle fleet requires bringing into production 55% more new mines. Between 35 and 195 large new copper mines would have to be built by 2050, at a rate of up to six mines per year. In heavily regulated environments like the United States and Canada, it can take up to 20 years to build one mine from scratch.

The baseline (no green energy transition) scenario supposes a more realistic, but still challenging 35 new copper mines, or one per year from 2018.

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Instead of fully electrifying the US fleet of vehicles, Simon suggests focusing on manufacturing hybrid vehicles, which require far less copper than electric vehicles — 29 kg vs 60 kg.

Going this route would not require major grid improvements and would have almost as large an impact on reducing CO2 emissions, the study found. Also, the likelihood of finding the copper needed to make hybrids is much greater than for electric vehicles.

A final takeaway from the report? There are enough copper resources on planet Earth; the concern is whether these resources can be mined fast enough to support baseline global development, then go beyond towards vehicle electrification and green energy.

The baseline scenario envisions about 1.69 billion tonnes of copper will be mined by 2050, which represents about a quarter (26%) of the total copper resource of 6.6 billion tonnes.

Going deeper underground would grow the resource to 89Bt, and 241BT may be recoverable from the sea floor.

New copper mines that came online between 2019 and 2022 took an average of 23 years to get from discovery to production, the study says.

Copper market

Demand

On the demand side, electrical grids need to be updated, and governments are embarking on large-scale infrastructure investments that are copper-intensive.

Along with the usual applications in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is now added demand for copper in electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, and energy storage.

Additional copper is being demanded by the electrification of public transportation systems, 5G and AI.

According to Nikkei Asia, prices are being buoyed by the need for more data centers to support the development of artificial intelligence, all of which will require copper.

The latest copper demand driver comes from the Ukraine, where the war with Russia is consuming tonnes of bullet cartridge casings made of brass, an alloy of copper and zinc.

The European Defense Agency says a NATO 155-mm artillery shell contains half a kilogram of copper, with Ukrainian forces firing up to 7,000 per day.

Supply

Copper may have come off the boil recently due to problems in China but the structural supply deficit is real and keeping prices elevated.

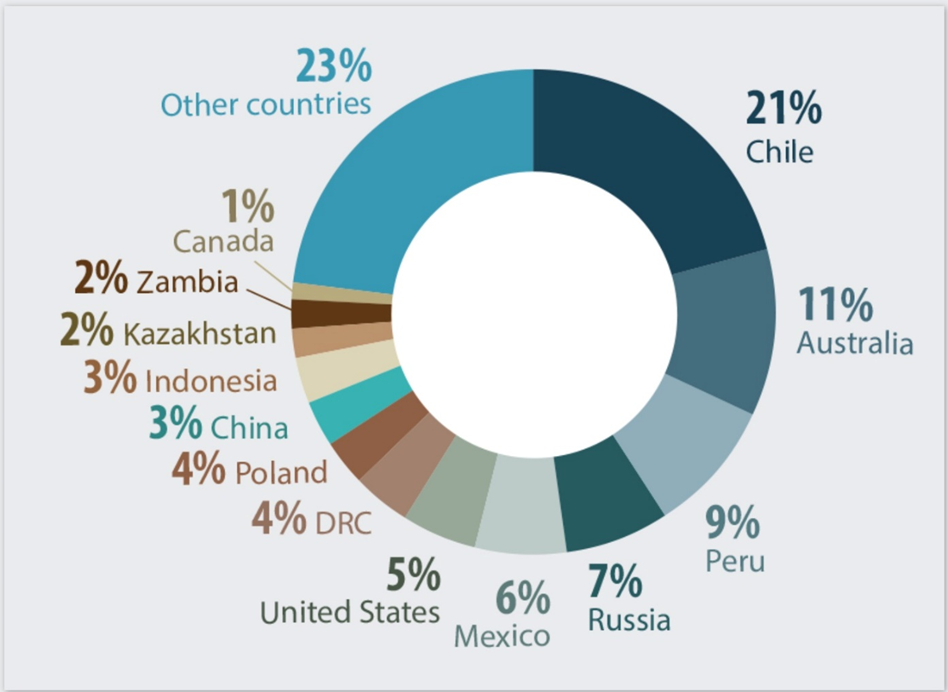

World reserves by country, 2022. Source: Natural Resources Canada

World reserves by country, 2022. Source: Natural Resources Canada

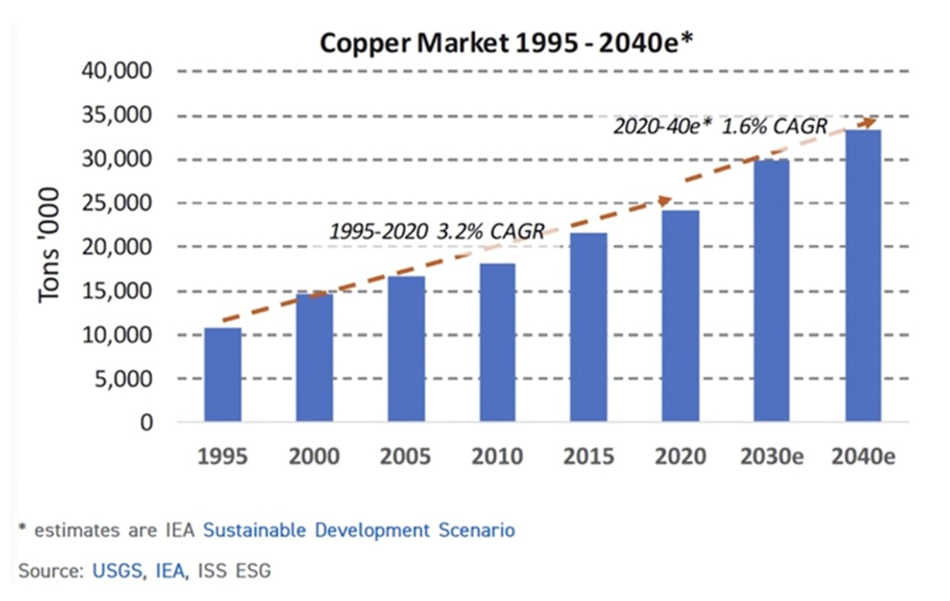

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) forecasts global copper consumption to grow 3.5% to 28 million tonnes in 2024, and for demand to increase from 27 million tonnes in 2023 to 38 million tonnes in 2032, averaging 3.9% yearly growth.

Yet the US Geological Survey reports supply from copper mines in 2023 amounted to only 22 million tonnes. If the copper supply doesn’t grow this year, we are looking at a 6Mt deficit.

Mining companies are seeing their reserves dwindle as they run out of ore. Commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg says the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution. If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all.”

Effectively, lower grades mean millions of tonnes more rock needs to be moved and processed to get the same amount of copper.

Last week, the vice president of US investment bank Stifel Financial Cole McGill presented data that corroborates Goehring & Rozencwajg, stating “If you look at grades at the top 20 copper mines since 2000, they’ve trended down about 15-20%, and if you take out some of the higher-grade African projects, that’s even lower.”

Sprott agrees that, Chile and Peru, the top copper-producing countries, are grappling with labor strikes and protests, compounded by declining ore grades. Russia, ranked seventh in copper production, faces an expected decline due to the ongoing war in Ukraine. Despite efforts by miners to ramp up production, many analysts anticipate a widening supply imbalance.

Major copper miners aren’t doing much to alleviate the problem. High-quality projects are increasingly rare and major new discoveries are lacking. The time from discovery to production averages 16.5 years.

To meet the increase in copper demand, copper majors are focused on extending the life spans and productivity of existing mines rather than carrying out more expensive, and risky, exploration and development of new (greenfield) projects.

E&MJ Engineering stated in its outlook for copper production to 2050, “The trend toward declining orebody grades and continued development of the pursuit of existing operations to exploit lower grade deposits is likely to continue, in the absence of high-grade project discovery.

A decline in ore grade results in higher operating costs due primarily to the amount and depth of material required to be mined and processed to produce the same amount of copper product. It is no surprise that both GHG emission intensity and energy intensity increase as ore grade decreases. There is a point of inflection, where below an ore grade of around 0.5% copper, the intensity of both metrics rises sharply.”

Given that many mines are fast approaching, if not already tackling, similar grades, this is a pressing problem. In its fiscal year 2020 commodity outlook, BHP, the world’s third largest copper producer, estimated that grade decline could remove about 2 million metric tons per year (mt/y) of refined copper supply by 2030, with resource depletion potentially removing an additional 1.5 million to 2.25 million mt/y by this date.”

Along with technical issues such as falling grades/ deteriorating ore quality, there is also supply pressure from growing resource nationalism.

According to Sprott, capital for the exploration and development of copper mines peaked at $26.13 billion in 2013. Since then, it has almost halved and remains low, with only $14.42 billion spent in 2022.

McGill told Bloomberg that between 2009 and 2016, copper supply grew at a CAGR of 3.5-4%. Since 2016, when copper priced bottomed at around $2-2.20/lb, the CAGR is around 1%.

Without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) predicts global copper mine production will drop to below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15Mt. Over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Last year, the government of Panama ordered First Quantum Minerals (TSX:FM) to shut down its Cobre Panama operation, removing nearly 350,000 tonnes from global supply.

A strike at another large copper mine, Las Bambas in Peru, temporarily halted shipments.

Copper specialist Anglo American says it is scaling back output by about 200,000 tons, owing to head grade declines and logistical issues at its Los Bronces mine. Los Bronces production is expected to fall by nearly a third from average historical levels next year as the miner pauses a processing plant for maintenance, Reuters said.

Chile’s copper output has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north. State miner Codelco’s 2023 production was the lowest in 25 years.

All four of Codelco’s megaprojects have been delayed by years, faced cost overruns totaling billions, and suffered accidents and operational problems while failing to deliver the promised boost in production, according to the company’s own projections.

There are also concerns about Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, where drought conditions have lowered dam levels, creating a power crisis that threatens the country’s planned copper expansion.

Ivanhoe Mines (TSX:IVN) reported a 6.5% Q1 drop in production at the world’s newest major copper mine, Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

The Congo last year overtook Peru as the world’s second-largest copper producer, but supply is threatened by ongoing armed conflict.

According to Voice of America

At least 70 people, including nine soldiers and a soldier’s wife, were killed when armed men attacked a village in western Democratic Republic of Congo, local authorities said, as violence intensifies between two rival communities…

The army is also struggling to contain the violence in the eastern part of the country, which has been torn by decadelong fighting between government forces and more than 120 armed groups seeking a share of the region’s gold and other resources.

Violence in the eastern part of the country has worsened in recent months as security forces battle the militias. Earlier this month, a militia attack on a gold mine in northeastern Congo killed six Chinese miners and two Congolese soldiers.

The World Health Organization warns that millions of people in the DRC are facing a health and humanitarian crisis (VOA, July 13, 2024)

As the government collects billions in revenues from new mining operations, like Ivanhoe’s Kamoa-Kakula, we predict the fight over resource rents could lead to internal struggles over who controls the government. How long before Congolese copper, cobalt, diamonds and gold are labeled “blood minerals”?

The forecasted copper supply gap — more than 15Mt by 2034 — was front and center at the Rule Symposium in Florida earlier this month. Mining magnate and Ivanhoe Mines’ founder Robert Friedland said current copper prices “fall woefully short” of supporting the development of new projects.

“We see a crisis coming in physical markets and a requirement for much higher prices to enable most of the copper projects that are in development to have a prayer coming in,” Friedland said via The Northern Miner. . The incentive price to build new mines is $11,000/t.

Higher prices are needed to counteract soaring cost inflation in building new mines, even in cheaper jurisdictions like Chile and Peru.

Friedland produced a surprising statistic, that humanity must mine more copper in the next 20 years than we have in human history to meet surging global demand on the back of the energy transition.

He estimated the global economy needs to find five or six new Kamoa-Kakula-sized projects yearly to maintain a 3% gross domestic product growth rate over the next two decades.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically. S&P Global estimates that new discoveries averaged nearly 50Mt annually between 1990 and 2010. Since then, new discoveries have fallen by 80% to only 8Mt per year.

There are really only three ways for the industry to get this additional metal. First, they can increase production from existing mines; this often involves “going underground”, and digging beneath the existing open pit to access more ore. An expansion to the existing concentrator or building a new one is sometimes needed.

Second, they can expand their mines laterally, going after resources that weren’t part of the initial mine plan because they were less accessible, or un-economic.

Third, they can explore for new mineral deposits, either internally, or working with junior mining companies, which have the exploration expertise to bring a deposit forward to the point when it can be sold to a major.

Obviously, option three, known as greenfield exploration, is more difficult, costly, and carries higher risk than options one and two, called brownfield exploration.

Prices

Crux Investor noted that copper prices have risen significantly, with majors like BHP acquiring copper assets through M&A rather than building new mines. Examples include BHP’s purchase of Oz Minerals and Newmont’s acquisition of Newcrest.

Gold, silver and copper had a banner first half — Richard Mills

Despite the market’s recognition of copper’s role in the future economy and increasing supply tightness, Crux Investor says analysis shows copper prices still remain below their long-term inflation-adjusted average, suggesting room for further appreciation.

While BMO Capital Markets and Citigroup analysts believe current copper prices may rise past $4.54/lb due to a Chinese smelter supply shortage, and grid investments in China, they say a sustained price gain is needed by copper miners to make investment decisions.

Copper mining is an extremely capital-intensive business for two reasons.

First, mining has a large up-front layout of construction capital called capex – the costs associated with the development and construction of open-pit and underground mines. There is often other company-built infrastructure like roads, railways, bridges, power-generating stations and seaports to facilitate extraction and shipping of ore and concentrate. Second, there is a continuously rising opex, or operational expenditures. These are the day-to-day costs of operation: rubber tires, wages, fuel, camp costs for employees, etc.

The average capital intensity for a new copper mine in 2000 was between US$4,000-5,000 to build the capacity, the infrastructure, to produce a tonne of copper. In 2012 capital intensity was $10,000/t, on average, for new projects. Today, building a new copper mine can cost up to $44,000 per tonne of production.

Capex costs are escalating because:

Declining copper ore grades means a much larger relative scale of required mining and milling operations.

A growing proportion of mining projects are in remote areas of developing economies where there’s little to no existing infrastructure.

Many inputs necessary for mine-building are getting more expensive, as cross-the-board inflation, the highest in 40 years, infiltrates the industry. This includes two of the largest costs, wages and diesel fuel, used to run mining equipment.

The bottom line? It is becoming increasingly costly to bring new copper mines online and run them.

Investors are also demanding a higher return on investment than previously, when there was a greater appetite for risk.

Citigroup is bullish on copper, with the bank’s analysts predicting that prices could surpass $10,000 a tonne ($4.53/lb) this year due to policy support in China.

Mining.com reports Beijing is expected to introduce further stimulus to upgrade its renewable energy infrastructure at the Third Plenum meeting in mid-July:

These additional measures, specifically targeting domestic property and grid investments, are expected to support copper prices in the near term, Citi analysts said in a note.

Conclusion

Copper presents a compelling opportunity for investors. The Sprott report notes that copper prices and miners are likely to benefit from the growing supply-demand gap. It also says that copper’s strategic importance has driven significant M&A in 2023, with BHP and Rio Tinto acquiring copper producers at significant premiums. Automakers concerned about securing future supplies are investing directly in mining companies.

But copper miners buying other copper miners does nothing to alleviate the supply shortage. It only transfers one copper reserve to another. Majors have underinvested in copper exploration and development, preferring M&A to the expense and risk of finding new copper deposits.

Junior copper explorers provide investors exposure to potential new discoveries that could help narrow the supply gap. These discoveries offer the chance for outsized returns, though obviously with higher risk.

Copper equities have underperformed the copper price, presenting a potential catch-up opportunity.

Extraordinary demand growth, set against a backdrop of constrained supply, is expected to deepen the structural deficit through the end of the decade. Higher copper prices will be needed to incentive new supply. (Crux Investor

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply