Ever notice how “home” is so important to our holiday traditions? It’s hard to imagine Christmas without images of a fireplace, a tree, some food, and rooms with festive decorations. Families gather in such rooms to form lifelong bonds and memories.

My neighborhood here in Puerto Rico really goes all out on Christmas decorations. There are more than a few snowmen and other winter decorations that make me smile.

Yet for many, having that kind of home is an elusive dream because our economy isn’t providing enough of them. Whether you want to buy or rent, finding an affordable, comfortable home can be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The basic reason is clear: Supply just can’t keep up with demand. But the factors behind this mismatch are proving more stubborn than they should. We should all be asking why this is such a problem, for two reasons.

First, a society in which everyone can find an affordable home is more stable, peaceful, and prosperous. And second, if the housing shortage isn’t already affecting you (or your kids and grandkids)… it will soon.

Over Thanksgiving, I learned that one of my kids had bought a nice home in Tulsa, high mortgage rates and all. It got me to thinking about the state of housing in the US.

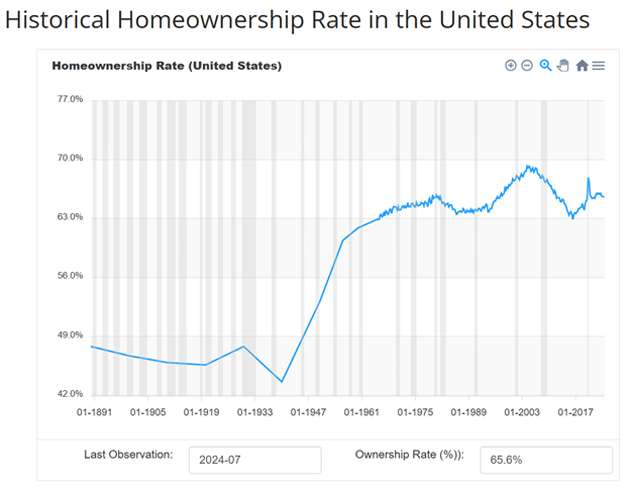

65.6% of Americans own their homes, roughly the percentage that it has been for the last 50 years, down slightly the last few years.

Source: DQYDJ

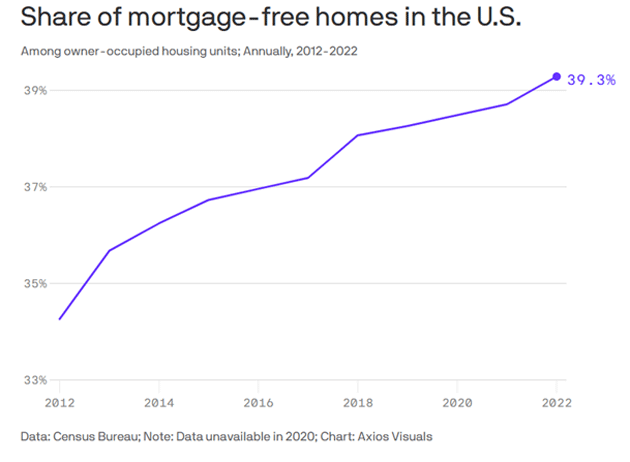

Almost 40% of homeowners own their home free and clear of any mortgage.

Source: Axios

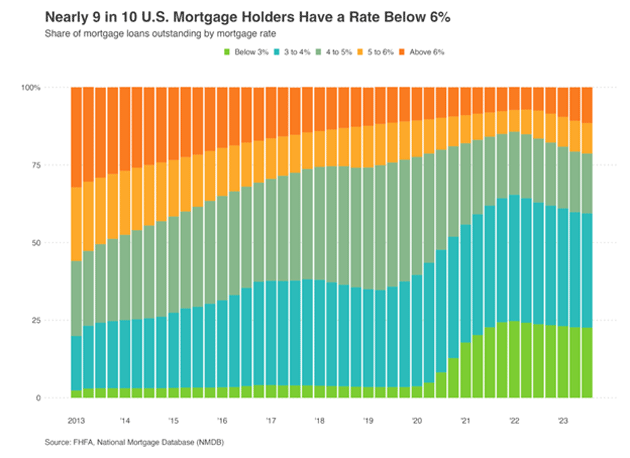

But of those with mortgages, most have rates significantly below the 6% that used to be normal.

Source: FHFA, National Mortgage Database (NMDB)

What that means is almost 60% of America has a mortgage below 4%. My kids felt they could handle the 6% mortgage. I smiled and remembered when I was about their age and I had a 12% mortgage. Things worked out. Admittedly, not the way I planned, but that’s another story.

What about those people that don’t own their homes or can’t afford one? That’s the problem that we will focus on.

I have a regular reader, someone quite famous whom I know personally, who agrees housing is a big problem. But whenever I write on this topic, he castigates me for not blaming the “oligarchs” whom he says are purchasing large numbers of homes, thus driving up prices and raising rents.

It is true that investors own many homes. By definition, every rental home is owned by someone who doesn’t live there. That’s what makes it a “rental.” This isn’t new and there’s nothing wrong with it. Rental property investors provide a valuable service, at no small risk to themselves.

Plenty of people don’t want to own the building in which they live, for all kinds of reasons. I didn’t own a home from the mid-’90s up until 2014. Renting was cheaper and more convenient.

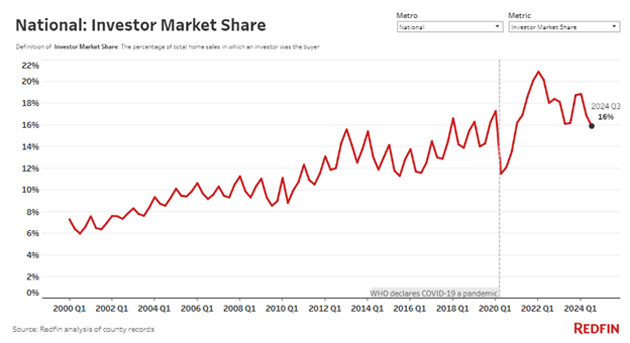

It’s also true that investors have been buying more homes. This goes back quite a few years according to Redfin’s data. Investors purchased 15.9% of all US homes sold in this year’s third quarter. That number, which has been rising for a long time, shot way up in 2021–2022 (when rates were lower!) but now seems to be returning to the previous trend.

Source: Redfin

It is less clear who the investors are. They range from individuals who own a handful of properties to large funds with thousands of homes, plus some relatively smaller mid-size investors in between.

The most comprehensive study I could find was this 2022 Congressional Research Service study, which cites 2021 research by the US Census Bureau and Department of Housing and Urban Development. They, in turn, looked at raw data from a 2020 survey. This is all a few years old but things haven’t changed all that much looking at recent less rigorous analysis. What does it say?

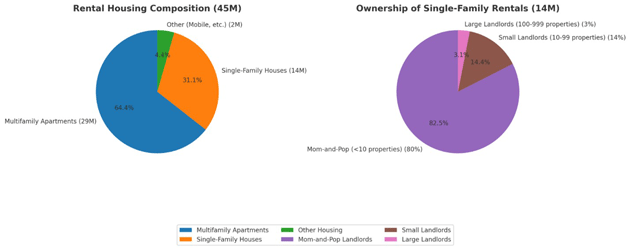

As of 2020, the US had 19.3 million rental properties which had 49.5 million rental units. Most of the properties were single units, i.e., houses. The rest were apartments, condos, etc. Individual investors owned 70.2% of the rental properties. These are, presumably, the traditional local landlords who own one or a few homes, perhaps as a sideline business. Think Airbnb, etc., which has become quite large. Clearly not oligarchs.

Single-family rentals are owned mostly by small investors, not giant corporations. The data suggests only about 3% are owned by landlords with more than 100 properties.

Source: Sunrise Capital Group

In fairness, this is hard to decipher because there are numerous categories of non-individual property owners: partnerships, LLCs, trusts, nonprofits, REITs, and so on. Some of these are probably individuals who, for estate planning or liability purposes, choose not to own their rental properties directly. There are over 2 million Airbnb listings in the US out of 7 million worldwide. This Rutgers report estimates that large institutional investors owned only 574,000 single-family homes as of June 2022. If so, it supports the other estimates of large investors owning only 3%–5% of rental houses.

Generally, though, the ownership picture is exactly what you would expect. Individual investors tend to own smaller properties like single-family homes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings. The various corporate structures tend to be larger developments. So, if we have an oligarch problem, that’s where it is. Except that it’s not.

These institutions are almost entirely just combinations of small investors. Who owns REITs? Pension plans, endowment funds, and regular people just saving for retirement. Wealthy investors are in there, too, but they aren’t necessarily in controlling positions.

This idea that oligarchs are monopolizing the housing market just doesn’t fit the data. Much of the commercial real estate today is owned by investment funds which are in turn owned by individuals or funds like teacher, police, and fire department pensions, insurance companies, etc. Yes, those managing those funds make a lot of money using what is called OPM—Other People’s Money. It’s America and called capitalism.

That said, there may be something else going on. It’s about technology, not ownership.

Setting rent used to be guesswork. Leaving a property vacant while you try to identify what the market will bear can be costly. Many owners would set a number that covered their costs plus a profit margin, then adjust occasionally. Modern software is giving landlords better information, often letting them charge higher rates.

A company called RealPage does this so well it is now being sued by the US Justice Department and eight states for alleged price fixing. The suit claims the company’s pricing algorithm “enables landlords to share confidential, competitively sensitive information and align their rents.”

To me, this doesn’t sound like cartel behavior. The landlords who use RealPage software aren’t meeting in a dark room to set artificially high prices. It’s more like the systems airlines and hotels use to make sure every seat/room is sold at the best possible price. As a frequent traveler, I can certify this is highly aggravating at times. But the good part is I can usually get where I want to go. Profits are what encourage more supply. Further, the same kind of technology also gives renters better information, helping them find lower rates. It’s a two-way street.

Nevertheless, this kind of optimization may boost rental rates in some places to a level they would not have reached otherwise. That’s frustrating for renters now but should also create more supply and eventually bring rates down… unless something else gets in the way—like local regulations and building codes.

We’re talking mainly about rental rates, not home purchase prices. This reflects a trend I think is not being sufficiently noticed.

In addition to the millions who simply can’t afford to buy, a growing number of higher-income people who would once have been homeowners are choosing to rent. I think many of these want to avoid maintenance hassles or don’t like being tied down. But others have concluded owning a home may not bring the financial rewards previous generations enjoyed.

Tax policy is part of the equation. For decades following World War II, states and the federal government tried to encourage home ownership with rewards like tax deductions for mortgage interest. This was essentially a subsidy available only to those who bought homes. Renters got nothing. “The American Dream” came to include a belief that paying rent was a waste and you should buy a house as soon as you could afford it.

The 2017 tax package changed this calculation. Among other things, it eliminated personal exemptions and sharply raised the standard deduction. With inflation adjustments, every married couple will get a $30,000 deduction in 2025 without needing to itemize. Median household income is around $80,000. This means paying mortgage interest or property taxes brings no additional tax benefit for most families.

Very few middle-class households have enough mortgage interest and other deductions to justify itemizing. They get the same deduction whether they rent or buy. We have thus removed what was once an important subsidy to homeownership. Maybe that’s the right policy but it’s changing the housing market.

We will see what new equilibrium emerges, but I expect renting your home will become far more common than it used to be, and homeownership less so—especially for the lower 80%–90% of the income scale. That process is already underway and is one reason rental demand is so strong in most of the country. We don’t have enough affordable homes to meet demand, and the construction that’s happening tends to be larger homes than middle-class families can handle.

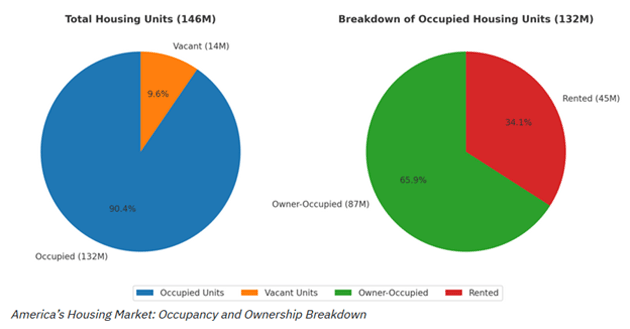

Here’s a look at the current housing supply—houses, apartments, everything.

Source: Sunrise Capital

The first thing that jumped out at me was the US has 14 million vacant homes. I had to look to find out what vacant actually means. Of course, apartments that don’t have a renter and homes that are vacant looking for a buyer are considered vacant. A second home that is only occupied a small part of the year can be counted as vacant. Seasonal homes like in resort areas or for migrant workers can be counted as vacant. Some big cities have large numbers of homes where no one wants to live.

The right graph shows that 34.1% of the non-vacant housing units are rented rather than owner-occupied. Many of these are the same kind of households that would always have rented—young singles, lower-income families, etc. But I suspect many are not, and this number may grow in the coming years.

Whether people rent or buy, everyone needs some kind of home. There’s a strong argument we are actually underestimating demand. The current shortage is forcing many into roommate situations and other arrangements they would prefer to avoid.

Others are delaying the “household formation” (i.e., marriage and childbearing) because they can’t find suitable homes. My friend Philippa Dunne recently cited a study showing that “normal” household formation in 2023 would have raised already-stretched housing demand by at least 3.4 million additional units.

My long-ago commodity business partner, Gary Halbert, used to say, “the solution to high prices is high prices.” He was talking about corn and soybeans. He was right—high prices entice farmers to plant more acreage and do other things to raise production, which then push prices back down.

That cycle unfolds over months in agriculture. Housing is different because houses take longer to build, and also because we “consume” them slowly over decades. But the law of supply and demand does eventually work unless external forces prevent it.

That’s where we are now: high demand, low supply. The shortage is not uniform across the country, though. Some rural areas have excess housing because jobs are so scarce. Meanwhile, stylish urban cores have plenty of housing if you are a wealthy executive or highly-paid professional. Regular people have no chance of living there, even as the well-heeled residents generate all kinds of demand for service workers. Those workers end up commuting from suburbs and exurbs, which in many places are also filling up, forcing new residents further and further out.

The obvious answer is to build more lower-end housing closer to the places that need workers. That is proving extremely difficult, often due to NIMBY (“Not in My Back Yard”) sentiment among current residents. They like where they live, they don’t want it to change, and they can afford the inconveniences their resistance generates.

The problem is that building codes and land-use regulations are blunt instruments. The National Association of Homebuilders estimates that regulations and government mandates add almost $94,000 to the cost of a new single-family home. This is on top of higher materials costs. The same study shows rising softwood lumber prices over the last 12 months have added $35,872 to the price of an average new single-family home and $12,966 to the market value of an average new multifamily home. That increase in multifamily value means that households pay $119 a month more to rent a new apartment.

Skilled construction labor is scarce and becoming more so. The laborers have the same problems, too. Where are they supposed to live? Every extra hour they spend commuting is an hour that further delays progress.

My daughter Abbi works for Habitat for Humanity. Her boss sent around data talking about the average home in the US, lamenting the lack of 1,400-square-foot starter homes. I found the source of his data. There is some fascinating info for you housing wonks, but to me it shows why there are so few starter homes. They just cost too much to build. Multifamily apartments are really the only way to reduce the cost per living unit.

For the first 12 years of my life, I lived with my parents and two siblings in a home that was less than 900 square feet. My friends across the street lived in a development of “large” homes that were almost 1,200 square feet. Whole neighborhoods like that were common from the late 1940s into the 1970s. That has gone away.

All this is solvable but takes time. And as time passes, costs get higher. People grow angrier and more frustrated. They do things that further delay solutions. And in the background is a ticking time bomb of government debt, the one I keep saying will explode into crisis.

Whenever the debt crisis hits, it will go better if we’ve solved the housing shortage and people are at least living in sustainable situations. We’ll have problems… but at least we’ll be able to go home for Christmas.

It was in the early 2000s and the beginning of my writing this letter. My readership was probably only about 10,000 and I still answered each email personally. I got an email from someone named Art Cashin who gently reminded me that it was Harry Markowitz, not Alfred Markowitz. I responded and we soon developed a more or less regular correspondence. It didn’t take me long to figure out who he was.

I mentioned I was coming to New York, and he asked me if I wanted to be on CNBC. I jumped at the chance and went down to the New York Stock Exchange to meet him and eventually be interviewed. I was nervous as hell and I am sure I fumbled it, but Art talking with the host later said, “He writes a very interesting free letter.” Literally, my numbers jumped. (I think that was how Richard Russell (of the Dow Theory Letters) found me, which also really boosted readership.)

Art’s father died when he was a senior in high school, so he went to work for a firm on the exchange at 18 years old in 1959. At 23 he became the youngest exchange member, telling me the next youngest member was in his 40s. UBS eventually made him their chief of floor operations, but his real role was the face of the Exchange on CNBC. UBS couldn’t buy better advertising.

Art was not only a mentor but became a close friend. I made a point to visit the Exchange every time I was in New York. On more than one occasion (this was when the Exchange was really going), we would walk through a crowded floor, and somebody would yell “Art! Come here. We have a problem.” It turns out that Art was something called a Governor and had the authority to settle trading disputes among members.

He would go over, hear two gentlemen argue over a (somewhat contentious) disputed trade, get both sides, and make a quick decision. Even if they weren’t happy, they always said, “Yes, Mr. Cashin.” I distinctly remember one dispute that was over a very small trade in an option on a very small microcap. It was also complex and quickly got out of my league.

Afterward, as we always did, we went over to Bobby Van’s where Art held court in the corner of the bar for what has always been called The Friends of Fermentation where they specialized in marinating ice cubes. They even had a plaque commemorating it. Art always drank Dewars and ice and always more than one. I once gestured at the really great scotches on the wall and asked why he didn’t drink one of them? “It’s what I’ve always drunk,” he said. And then he would tell the story of how his tuition bill was picking up the bar tab for senior traders. I guess they drank Dewars and that was his way of staying connected. God he could tell stories. The best stories. 60 years on the Exchange gave him awesome stories.

On that occasion, I remember asking one of the members about Art’s actions on the floor that day. I was told that he treats every situation exactly the same, no matter who or the size. Which is why he was made a permanent Governor. He was essentially the sheriff of the New York Stock Exchange.

He could listen to the sound of the Exchange and tell you what was happening. Not many people know that during 9/11 and the financial crisis he was consulted at all levels of the Exchange. He had that level of respect. He brought wisdom and calm in the midst of the storm.

Art wrote a daily letter called Cashin’s Comments. It always had a historical story that tied into what happened in the markets that day. He was a prodigious reader of history and remembered everything. I used to send out his letters frequently to what was then a million subscribers. I always got back comments of, “Where does he come up with all these incredible stories?”

I think of all the stories and times that I spent with Art. The literally scores of dinners where a rotating few of us would gather, share ideas, and listen to Art’s stories. And watch him drink Dewars. He would always leave early, putting $200 cash on the table and Peter Boockvar would hold his change until the next dinner. Peter told me a few years ago, at the last dinner, Art kept the change. He clearly knew. He had a physical condition that was slowly getting to his body. He visibly deteriorated somewhat when both his wife and daughter died in a relatively short time. But he never complained. He was Art.

Today of course, the Exchange is a shadow of itself. With computer trading, we no longer have an individual whom you can look in the eye and can settle disagreements. There is no sheriff.

His passing represents the end of an era, and I and so many of his friends will miss him. I am sure there are many gatherings in his memory, but some of us will gather in New York in 10 days. We will tell some of his stories and perhaps share a round of Dewars and ice. I think we will all pay more attention to those sitting with us. It does go so quickly. But yet, we can take joy in that somewhere in the heavenly halls, in a corner where the Friends of Fermentation are gathering, Art will join us and order another round. I am sure the Dewars will taste better.

I dedicated one of my books to him with: “To Art Cashin—Greatest of Raconteurs, Finest of Teachers, Best of Friends.”

Rest in peace, my friend.

For those interested, my friend Danielle DiMartino Booth did this interview with him a few years ago in Bobby Van’s, that is now on YouTube.

And here is my friend and fellow Friend of Fermentation member Barry Ritholtz’s tribute.

I will be at the rather large Longevity Fest in Las Vegas from December 13–15 before heading to New York for a few days of dinners and meetings. If you are attending that longevity conference, drop me a note and let’s meet. I will be in Austin the first week of January and then later that month in Newport Beach.

And with that, I will hit the send button. Have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on X!

Your missing fallen comrades analyst,

|

John Mauldin Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply