With the price of gold rocketing and with gold re-establishing itself as the leading monetary reserve asset for central banks worldwide, the quantities of physical gold held by each central bank and the locations of those reserves are becoming increasingly critical questions.

While most have heard of the Bank of England’s fabled gold vault in London and the New York Fed’s deep underground gold vault in Manhattan — both preferred storage facilities for central banks — did you know that four central banks from Europe claim to store a substantial amount of gold with the Bank of Canada in Ottawa?

These are the central banks of the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden and Belgium, known respectively as De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the Swiss National Bank (SNB), the Swedish Riksbank, and the National Bank of Belgium (NBB). And the amount of gold that these four central banks claim to hold in Ottawa is not insubstantial, totaling approximately 270 tonnes.

Like nearly everything in the opaque and secretive world of central bank gold, these four central banks had been, for many years, quietly keeping their heads down, never revealing that portions of their national monetary gold holdings were supposedly being stored in Ottawa.

But then a perfect storm of factors aligned that forced them to break the secrecy, factors which interplayed and triggered increased expectations for gold holdings transparency — the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 which intensified scrutiny on central banks; the European Debt Crisis of 2010–2012 which spurred demands for transparency in monetary reserves; political pressure and calls from state auditors for gold holdings disclosure; public activism pushing for gold repatriation and domestic gold storage; and finally the German Bundesbank’s high-profile decision that emerged in 2012 to repatriate some of its gold from storage in New York and Paris.

Swiss, Dutch, Swedish and Belgian

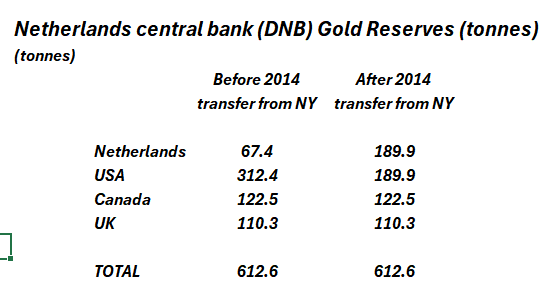

In the case of the Netherlands central bank (DNB), the trigger to reveal the location of its gold reserves came from Dutch members of parliament who in December 2012, noticing that the German Bundesbank was being pressured into explaining if its enormous gold holdings at the New York Fed were actually there, forced the then Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem to reveal that 51% of the DNB’s 612 tonnes of gold was claimed to be held at the New York Fed, 20% of the gold at the Bank of Canada in Ottawa (i.e. 122.5 tonnes), 18% at the Bank of England in London, and the rest stored domestically in the Netherlands.

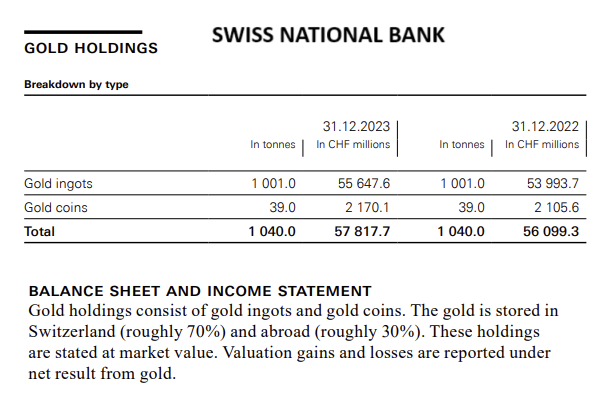

In the SNB’s case it was the “Save Our Swiss Gold” campaign, a national referendum initiative that spanned 2013 — 2014 which among other things called for a ban on SNB gold sales and the repatriation of all Swiss gold reserves stored abroad. In fighting this referendum, which it was successful in doing, the SNB’s then president, Thomas Jordan, in April 2013 was forced to reveal the previously confidential information that only 70% of the SNB’s 1040 tonnes of gold reserves were held in Switzerland, with 20% of the gold held at the Bank of England, and 10% of the gold held with the Bank of Canada in Ottawa (equivalent to 104 tonnes).

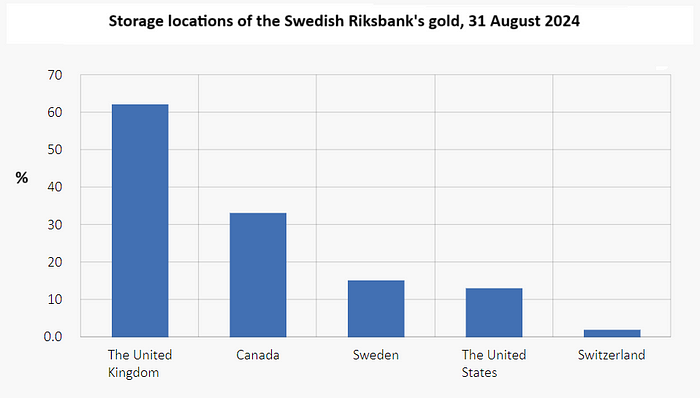

In October 2013, the Swedish Riksbank, up until then secretive about where its gold was located, also revealed that just under half of its 125.7 tonnes of gold was stored at the Bank of England, with another 33.2 tonnes (26.4%) stored with the Bank of Canada in Ottawa, and the rest stored at the New York Fed (10.5%), Swiss National Bank (2.2%), and domestically at the Riksbank (12%).

While the Riksbank at the time said that its new found openness was “part of the Riksbank endeavours to be as transparent as we can”, the real triggers for the Riksbank revelation were peer pressure from other European central banks (for example, in neighbouring Finland, the Finnish central bank revealed the location of its gold reserves during the same week as the Riksbank), and of course the by then in progress German Bundesbank gold repatriation operation from Paris and New York which began in 2013.

Turning to Belgium, following a series of parliamentary questions put to the Belgian Minister of Finance, Koen Geens, during the March 2013 period about the storage locations of the NBB’s gold (in light of the move by the Bundesbank to repatriate some of its gold), Geens reluctantly revealed that of the 227.5 tonnes of gold held by the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) “the largest part of the gold stock of the NBB is held at the Bank of England. A much smaller quantity is held at the Bank of Canada and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). A very limited quantity is stored at the National Bank of Belgium.”

While this answer did not state how much NBB gold was stored in each location, other media reports from 2014 stated that the NBB held 200 tonnes of gold in London. That being the case, if just less than half the remaining was held by the Bank of Canada (with the rest held by the BIS and domestically by the NBB), that would imply approximately 13 tonnes of Belgian gold claimed to be held in Ottawa.

More than 270 Tonnes of Gold

Adding together all the Swiss, Dutch, Swedish and Belgian gold claimed to be held at the Bank of Canada in Ottawa yields the following: 10% of Swiss gold holdings of 1040 tonnes = 104 tonnes; 20% of Dutch gold holdings of 612.5 tonnes = 122.5 tonnes, Swedish gold 33.2 tonnes; Belgian gold 13 tonnes; for a grand total of 272.7 tonnes, which would be approximately 8.768 million troy ozs of gold, and if in the form of Good Delivery gold bars (400 oz bars) would equate to 21,816 gold bars.

This 272.7 tonnes is quite a sizeable quantity of gold, and to put it into perspective, is approximately equal to the gold holdings of either the Austrian central bank (280 tonnes) or the Spanish central bank (281 tonnes), but has flown totally under the radar among the mainstream financial media. For example, not one mainstream financial news reporter has ever picked up on this topic and asked these four central banks about their gold reserves supposedly stored in Ottawa.

Historic Holdings in a Subterranean Vault

And here is where it gets interesting. The Bank of Canada was a historical gold storage custodian for central bank gold that primarily emerged as a safe place to store gold during World War 2. But its popularity dies down again dramatically from the 1950s onwards. The fact that some of the national monetary gold holdings of the Swiss, Dutch, Swedes and Belgians are claimed to be still held in Ottawa means that the gold in question has been there for a very very long time. For over 80 years to be precise.

Compared to far older central banks, the Bank of Canada was only established in 1935, and its headquarters building on Ottawa’s Wellington Street was only completed in 1938.

This Wellington Street building included a gold vault in the basement, described in the Bank’s head office plans as “a subterranean vault built right into the Laurentian Shield” (i.e. the bedrock). The gold vault, like the HQ, also opened in 1938, and had special shelving added to store the gold, and which one Bank of Canada employee said was “as cavernous as Fort Knox”.

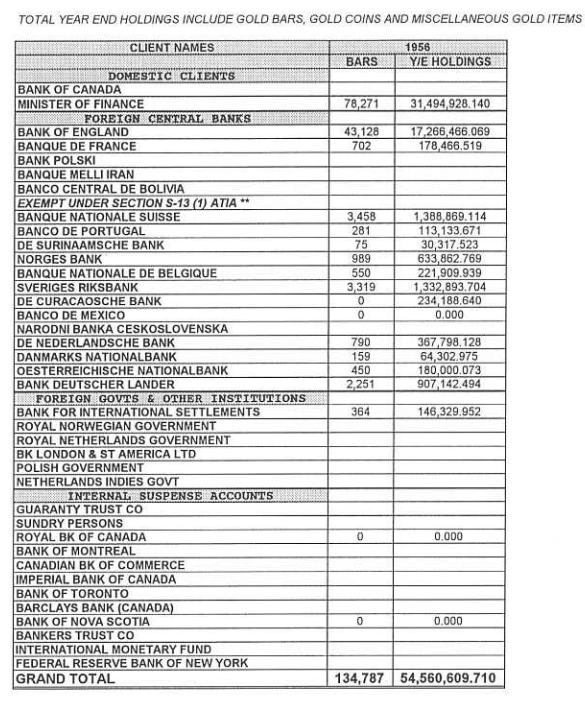

The first three foreign central banks to hold gold with the Bank of Canada were the BIS (1935), the Bank of England (1936), and the Banque de France (1939). Then as World War II broke out in 1939, a further eight central banks clients moved gold to Canada in 1940 to keep it out of reach of the Axis powers, including the Netherlands central bank, Norway’s central bank, and the Polish central bank. Then in 1942, the Swiss National Bank and Portuguese central bank began storing gold in Ottawa, followed by the National Bank of Belgium in 1943, the Swedish Riskbank 1944, and the Bank of Mexico in 1945. So can can see straight away how far back in time these gold holdings of Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden and Belgium in Ottawa stretch.

As the Bank of Canada historic documents explain, the European central banks during World War 2 looked at “the sanctity of Ottawa as a safe haven” and considered Ottawa “a faraway, safe place to store gold”. Which is why at its peak, the Wellington Street vault stored more than 2,500 tonnes of gold.

While a few more European central banks opened gold accounts at the Bank of Canada in the 1950s, e.g. Austria and Denmark in 1951, and West Germany in 1954, when the world returned to peacetime in the 1950s and following the end of gold convertibility in August 1971, most of these central banks ceased to have any gold holdings in Canada, except strangely the ‘Stay-Behind Quartet’ of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Belgium. The question is, why did these four central banks not bring their gold back from Ottawa to Europe like most other central banks did?

2012: The Gold Goes Walkabout

What’s even more puzzling is as follows. The Bank of Canada’s gold vault used to be located under it’s headquarters building on Wellington Street in downtown Ottawa. However, this building underwent a total renovation between 2013 and 2017 during which time it was literally gutted and the Bank’s 1400 staff moved to other locations. But not only the staff were moved. The gold was also moved.

As well-known Canadian magazine Maclean’s stated in an article titled ‘The Bank of Canada’s move, and what it means for a fabled underground vault’ in June 2013:

“The renovations, with a price tag of $460 million, and due to be finished by January 2017, will be so extensive as to require the bank to move the entire contents of its Wellington building, including the subterranean vault, which extends from below Wellington and, reportedly, out under the Sparks Street Mall.”

MacLean’s continued:

“Former front-line employees interviewed by Maclean’s, whose work until recently took them beneath the Bank of Canada building, describe vaults that, although depleted, continue to be home to a not insignificant horde of foreign reserves — gold in the form of bullion and coins kept for other central banks. Whatever those holdings entail, all of it is already gone, relocated in advance of the move.”

So you see, the gold that the central banks of Switzerland, Netherlands, Sweden and Belgium claimed over the years 2012–2017 to be “at the Bank of Canada in Ottawa” (Netherlands) or “held with the Bank of Canada in Ottawa” (Switzerland) or “held at the Bank of Canada” (Belgium), was not actually being held at the Bank of Canada ‘s vault in Ottawa. Whatever gold had been there was moved somewhere else. However, at no time did any of the four central banks change the language in their annual statements nor mention the fact that the gold in Ottawa, if it was there at all, moved out of the Bank of Canada’s vault.

When the Bank of Canada moved back into its renovated headquarters building on Wellington Street, there was also absolutely no mention that the vault still existed.

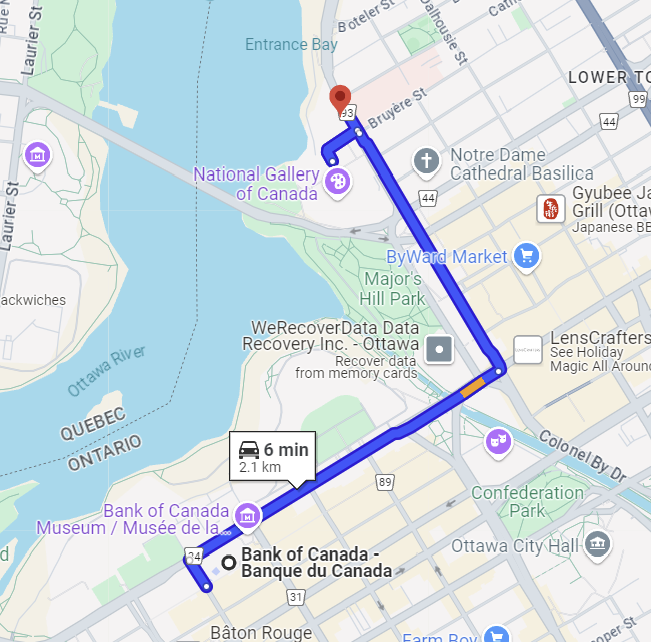

One possibility is that whatever gold bullion had been stored in the Wellington vault before the building renovation was transferred to the Royal Canadian Mint (RCM) on Sussex Drive, which is only 2 kms away from the Bank’s Wellington Street building, and about 5 minutes drive. This theory is plausible because a) the locations are very near each other in central Ottawa, b) both institutions are government organisations known as ‘Crown Corporations’ and c) the RCM, being a precious metals mint and a refinery, already had precious metals storage vaults.

We also know for a fact that in late 2012, a large number of old gold coins that had been stored in the Bank of Canada vault under Wellington Street for over 75 years up until that point, suddenly appeared in the vaults of the Royal Canadian Mint on Sussex Drive. These are coins that had been minted between the years 1912–1914, and some of which the RCM then offered for sale to the public as collectors’ items.

Not only that but as part of the publicity around these old gold coins, the then governor of the Bank of Canada, Mark Carney, appeared in publicity shots with the president of the RCM, Ian E. Bennett, in a precious metals vault at the RCM’s facilitates. While in the photos it just looks like working stock gold bars in the background on the shelves, the fact that the Bank of Canada’s collection of gold coins ended up in the RCM facility suggests that the foreign central bank gold might have been transported there also. If so, what became of the gold bars belonging to the Swiss, Swedes, Belgians and Dutch in the years following 2012?

Having foreign central bank gold reserves stored in a working precious metals mint and refinery is by definition very concerning because it opens up the possibility that the custodian (Bank of Canada) would allow the sub-custodian (Royal Canadian Mint) to borrow precious metal and use it in the gold coin production process.

In general, it is also concerning that supposedly sophisticated central banks such as the SNB, DNB, NBB, and Riksbank, would still entrust some of their extremely valuable gold holdings to a central bank (the Bank of Canada) that hasn’t even got any gold holdings of its own. That’s right! Because the Bank of Canada is infamous in having sold all of its huge gold holdings during the late 1980s, and into the 1990s, and into the early 2000s.

In 1985, Canada still held 625 tonnes of gold. But then between 1986 and 1994 (all through the Mulroney and Chrétien governments), Canada (via its Department of Finance) sold a massive 504 tonnes of gold, and by 1994 the State only held 123 tonnes of gold.

By year-end 2002, this total had dwindled further to a mere 18.6 tonnes, and by December 2003, Canada had no gold bullion at all, becoming, as Reg Howe phrased it “the world’s only major economic power to have eliminated its gold reserves”. Interestingly, Ian E. Bennett, the former RCM president in the photo above with Carney, held senior positions in Canada’s Department of Finance between 1984 and 1993, i.e. all through the period during which Canada sold its gold reserves.

Who then would trust a central bank (Bank of Canada) to safeguard their gold holdings when it (and the Canadian Department of Finance) had treated their own gold reserves like a clearance sale at the mall? But incredibly, as we have seen, the Swiss, Dutch, Swedes and Belgians central banks appear to have done so.

While the reason given by the Canadian authorities for selling the gold was to invest the proceeds into interest-bearing assets – itself a huge mistake given the huge rise in the gold price since then – there are various theories that the real reason for selling the Canadian gold was either as part of an internationally coordinated gold price suppression scheme, or as part of a bullion bank rescue operation that needed to pay back out of control gold loan losses.

So perhaps the Canadian custodied gold of the Swiss, Dutch, Swedes and Belgians went the same way, and that gold is now ‘on the books’ of their balance sheets as a smoke and mirrors line item ‘Gold Receivables’. In a similar vein, perhaps the gold of the Swiss, Dutch, Belgians and Swedes has long ago been leased, loaned, encumbered, pledged in loans and swaps, or even driven down to the New York Fed vault in Manhattan — a road which is less than 500 miles away from Ottawa and takes less than 7 hours.

Conclusion

Which brings us back finally to the central banks themselves, and the ways, not surprisingly, in which they have provided misinformation, disinformation and deflection about the true state of the gold reserves which they claim to hold in Canada.

In 2014, the Swiss National Bank published a document called “Arguments of the SNB against [The Swiss Gold] Initiative” in which it stated that:

“The same standards are applied to storing gold abroad as to storing gold in Switzerland. The partner central banks keep clearly identifiable gold bar holdings for the SNB. Each bar stored abroad has a bar identification and remains the property of the SNB. The availability of our gold holdings is fully guaranteed at all times.”

Given that there was no gold in the Bank of Canada’s Wellington Street vault in 2014, this quote from the Swiss National Bank is clearly untrue and is at best misinformation. The SNB also said that gold reserves need to be stored where there is “good market access”. As regards the claimed gold at the Bank of Canada, this statement is patently absurd. There is no central bank gold trading market in Ottawa, and remember the SNB claims to have 104 tonnes of gold in Ottawa. Ottawa is a central bank gold market backwater and hasn’t been a major gold trading centre for many decades.

In October 2014, the SNB also released a media dossier (only in French and German) in the form of a Q & A format (see here), one of the Q&As of which was as follows:

Q to SNB : When was the last visit of the SNB to these sites (abroad)?

SNB A: Representatives of the National Bank inspect the storage rooms of gold at regular intervals and in agreement with the central bank partners. The SNB has been satisfied in all respects by the result of these visits.

Again this is clearly not true as the gold wasn’t even at the Bank of Canada’s Wellington Street vault in 2014.

Likewise, in 2013, in a Q&A with Swedish media publication ‘Dagens industri about the Swedish gold reserves, the Riksbank answered as follows:

Q to Riksbank: “How do you verify that the gold is really where it should be?

Riksbank A:“We have our own listings of where it is. We reconcile these against extracts that we receive once a year. From now on, we will also start with our own inspections.”

Again, how could the Riksbank start its own inspections of the claimed 33.2 tonnes of Swedish gold stored in Canada, when all of the gold that had been in the Wellington Street vault in Ottawa had been moved out in late 2012? And as you can see there was no mention of the transfer out of the vault in the answer given by the Riksbank.

In 2017, I asked the Riksbank by email: “Is there any specific reason why the Riksbank does not publish a gold bar weight list in the way, for example, that a gold-backed ETF does publish such a weight list every trading day?

The Riksbank Head of Communications, answered as follows: “This kind of information is covered by secrecy relating to foreign affairs, as well as security secrecy and surveillance secrecy.”

So you can see that there are many problems with these central bank explanations. Take your pick, but here are a few.

The Riksbank refused to provide a gold bar list. The Swiss National Bank created huge push back against a popular initiative to bring Swiss gold back from Canada and London.

The Netherlands central bank in November 2014, in an announcement which caused great media interest, said it had secretly repatriated 122.5 tonnes of gold from the Federal Reserve vault in New York back to Amsterdam. But … if repatriating gold was so important to the Netherlands central bank at that time, why didn’t it use the logistical opportunity to also bring gold back from Canada in 2014 at the same time that it brought gold back from New York. After all Ottawa is only a few hours drive from New York?

And as regards the National Bank of Belgium (NBB), in early 2015 there was controversy about whether NBB governor Luc Coene had said that the bank wanted to repatriate 200 tonnes of gold from London. This was first reported by one Belgian newspaper as being true, and then reported by another Belgian newspaper as not being true, quoting Coene as saying that “The repatriation from the UK is not true”. But the point to note here is that none of the reports even mentioned the NBB gold claimed to be stored in Canada.

It’s as if in all of these cases, Canada has been conveniently and deliberately forgotten. And none of the four central banks that claim to have gold stored in Ottawa have ever repatriated a single troy ounce of gold from Canada, let alone a few gold bars. Why not? Where is the Netherlands’ 122.5 tonnes of gold? Switzerland’s 104 tonnes? Sweden’s 33.2 tonnes? And Belgium’s ~ 13 tonnes? That’s in total 272 tonnes of gold and nearly 22,000 good delivery gold bars.

In the current gold landscape, there are many central banks across the world increasingly holding their gold domestically and indeed repatriating gold reserves to their home countries (as seen with Poland, Hungary, and India). And also calls for the banks to justify why they maintain gold holdings abroad in the first place.

But at the same time, amid lack of transparency, lack of accountability and utter secrecy, the true state of the gold reserves of four foreign central banks in Canada remains unclear. This is indeed a very Curious Case. Has the gold gone AWOL ,or is there an innocent explanation? Enquiring minds would like to know.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply