Here in the US, people are obsessed with the impending election. It is perhaps the World’s Largest Guessing Game. We can look at polls and make our best guesses, but no one really knows what will happen. We just have to wait for more data which will (hopefully) be forthcoming November 5 or soon afterward.

Meanwhile, other things are happening in the world. Some have economic significance equal to our election. They are setting the conditions our new president will face… and nowhere are they more important than in China.

We don’t talk about China enough. I suspect this is for several reasons. First, because the country is so incomprehensibly big and populous. Second, it has been an economic miracle. Many Chinese enthusiasts just see a straight line projection of their growth. To the moon, Alice!

It’s just really hard to wrap your mind around everything happening in China. A lot of it is contradictory, too. Chinese government, business, and culture aren’t necessarily on the same page.

So, at the risk of only skimming the surface, today we’ll look at where China stands these days. But first…

For weeks now, I’ve been talking about our new longevity and biotech letter. Well, the wait is over. A big “thank you” to the over 10,000 readers who signed up to be on the waitlist. Your enthusiasm for this project means a lot to me.

Because this concerns something near and dear to my heart, I want you to be among the first to see what the team has cooked up. I’ve recorded a special announcement video from my home in Puerto Rico. You can give it a watch here.

Let’s start with the big picture. Over the 40 years or so since Deng Xiaoping, China made a historically remarkable leap from widespread poverty to industrial prowess. Other countries have gone through this cycle, of course, but none so large and certainly not so fast.

This had many global effects, including a massive boost to commodity demand. A growing but resource-constrained China imported vast amounts of energy and raw materials, which were then transformed into infrastructure, housing, and most of all exports to the West, often at prices low enough to render others uncompetitive. Chinese creativity, resourcefulness, and an impressive ability to “scale,” combined with what used to be cheap labor gave them a massive Ricardian comparative advantage.

At the same time, China transformed internally as rural farm workers took factory jobs in gleaming new cities. Living standards improved, at least near the coast, further boosting consumer goods demand. The nominally Communist government seemed to be seeking a new path of “communism with Chinese characteristics.” Cue fawning economists.

China’s growth eventually produced conflict with its customers, contributing to the populist surge that made Donald Trump president in 2017. The next three years were a kind of low-grade trade war as Trump imposed tariffs and other restrictions on China while at the same time trying to negotiate better trade terms.

We don’t know where that would have led because COVID intervened. Perhaps someday we will get the full story of how this virus originated and spread within China, but it will not happen for a while. The Chinese government’s reaction suggests those early months were terrifying. Whatever Xi Jinping saw convinced him to clamp down hard, essentially shutting down the economy. And not just for a few weeks, but for the next three years.

China emerged from COVID lockdowns (which were far more restrictive than anywhere in the US) less than two years ago. That’s really not much time to recover. In some ways, it’s a kind of Rip Van Winkle story: You have a long sleep and wake up to a different world.

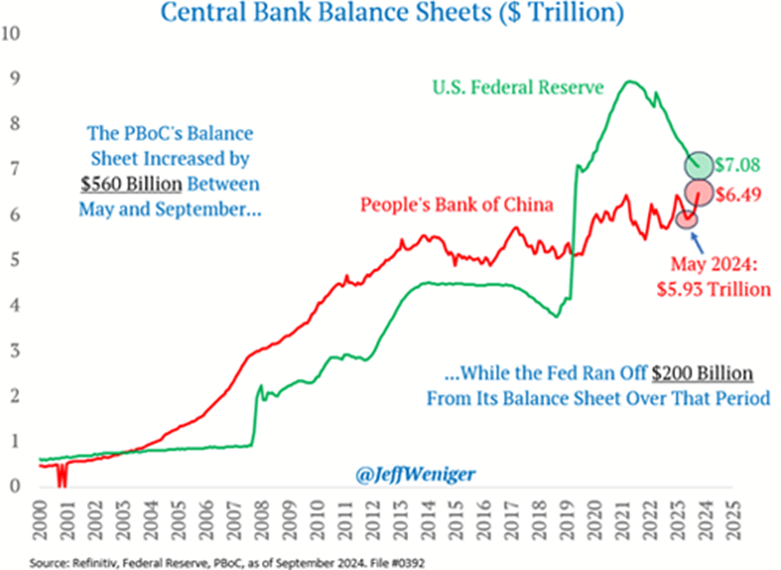

As happened elsewhere, the Chinese government is trying to kickstart the economy with fiscal and monetary stimulus. To some degree, this isn’t new. The People’s Bank of China has been expanding its balance sheet almost without interruption for 20+ years.

Source: Jeff Weniger

Notice two things in this chart. First, in dollar terms the PBOC’s balance sheet is almost as big as the Fed’s even though our economy (using nominal GDP) is around 60% bigger. China’s central bank is stimulating far more than ours, relative to the size of each economy.

Second, they’re going in different directions. Since May the PBOC added $560 billion in assets while the Fed reduced $200 billion. Why?

Each institution faces different situations but they’re also at different points on the timeline. The US began emerging from the worst COVID restrictions in 2021. China took two years longer, so it makes sense the PBOC isn’t at the same place yet.

But it’s probably not the central bank we should think about. China’s commercial banks are a much bigger concern.

Back in 2021 I wrote a letter called China’s Gilded Age Is Over. That was the scary period in which property developer Evergrande defaulted on some debts and would later go bankrupt. Other developers had similar problems. But as we all know, lenders usually end up holding the bag in these situations. That makes it a government problem.

This month Beijing unveiled a ¥1 trillion stimulus package, one element of which is for the government to buy bonds issued by six large state-owned banks. The odd part is these aren’t the banks having problems. My friend Michael Pettis posted this note:

“The banks that will receive the capital injections are Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Bank of China, the Agricultural Bank of China, Postal Savings Bank, and BOCOM (the Bank of Communications).

“It is interesting that these are among the best capitalized banks in China with the least impaired balance sheets. The smaller regional banks, who control the bulk of non-performing or impaired assets, will not be included in the recapitalization.

“I suspect that this implies that after many years during which the credit allocation process had been decentralized towards regional banks, Beijing is interested in re-centralizing the banking system and taking greater control of credit allocation.”

What’s going on here? I view this as another step away from “capitalism with Chinese characteristics.” The regime seems to be learning that banks, left to their own devices, often get overextended. Particularly when they don’t have the kind of guardrails and institutional memories we do in the West, and particularly when they are encouraged and indeed incentivized to do so by local governments. Xi’s solution is to let the weak banks fade away while positioning the big state-owned banks to take a bigger role.

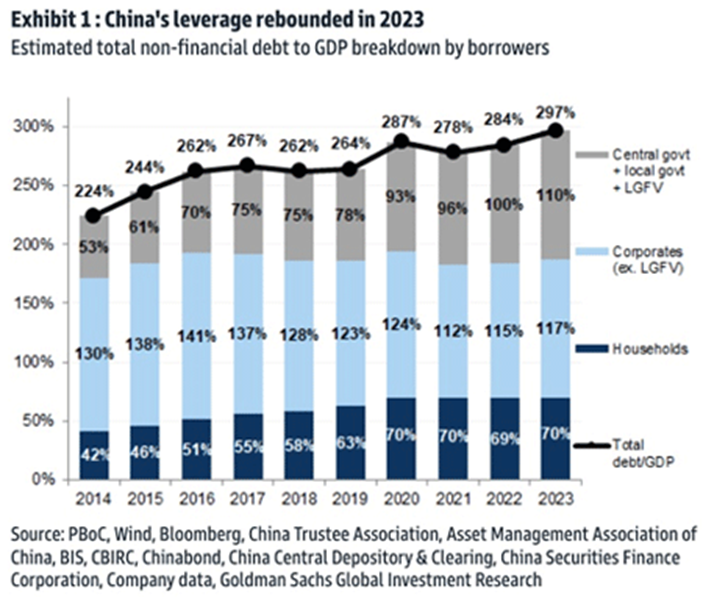

But the problem with bad debt is you can’t make it disappear; you can only move it into different hands. To an autocratic leader, this makes sense. Keep the potential problems under close control. But Xi has much bigger problems than real estate loans. Total debt in China—government, corporate, and household—is now approaching 300% of GDP.

Source: Financial Times

Look closely and you’ll notice the debt growth is concentrated in government. Household debt has been steady since 2020, and corporates actually deleveraged. I suspect some of this represents the government taking bad debt from the others onto its own books. Bailouts, in other words. They don’t break out how much of the debt is the national government vs. local ones, but the latter is significant.

Even more of that private and corporate debt will likely end up on government balance sheets. A lot of that corporate debt is real estate. From the NYT:

“China has a housing problem. A very big one. It has nearly four million apartments that no one wants to buy, a combined expanse of unwanted living space roughly the area of Philadelphia.

“Xi Jinping, the country’s leader, and his deputies have called on the government to buy them.

“China has a bigger problem lurking behind all those empty apartments: even more homes that developers already sold but have not finished building. By one conservative estimate, that figure is around 10 million apartments.

“…One recent estimate, from the research firm Rhodium Group, put the real estate sector’s entire domestic borrowings, including loans and bonds, at more than $10 trillion, of which only a tiny portion have been recognized.”

The average vacancy rate is 12%. Many families own 2 and 3 homes, which they see as a kind of savings account. This is not unlike the US in the housing bubble. One difference, though, is that many Chinese families only have one child. It isn’t unusual for the parents to own two homes and for the child to own one or even two homes. Savings, you know?

Understand, the Chinese are seriously frugal savers. There is no safety net, no Medicare or Social Security. Housing is considered a form of savings. The Chinese stock market has not been as friendly as the US stock market. And for 30 years, housing was indeed a form of savings, until now it’s not.

That’s bad enough. But in the grand scheme of things, China has even bigger problems.

I’ve talked before about China being in an even worse situation than Japan. Both face an aging population problem, but Japan was at least able to get rich before it got old. China is getting old faster than it is getting rich. And as noted above, some of the savings are evaporating.

It’s no wonder the government and Xi Jinping are wanting to stimulate the economy. But unfortunately, the economy is already overstimulated and debt is rising. It’s a lot like trying to cure an alcoholic by giving him higher-quality whiskey.

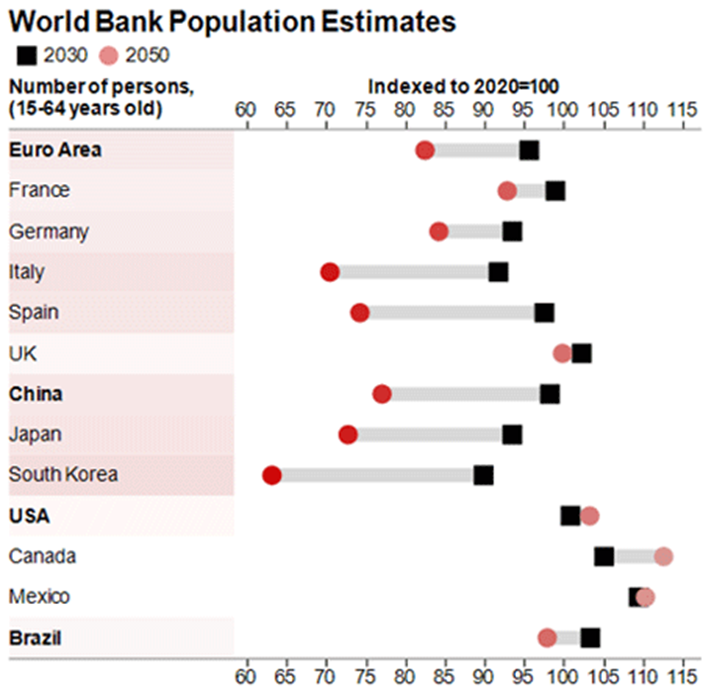

Here’s an interesting chart from my friend Karen Harris at Bain. It compares projected working-age population change from 2030 (the black squares) to 2050 (the red circles), indexed so that 100 represents the 2020 level.

Source: Bain Macro Trends Group

By 2050, China’s working-age (15–64) population will have shrunk by about 25% from the 2025 level. Japan and South Korea will shrink even more, but they’re much smaller.

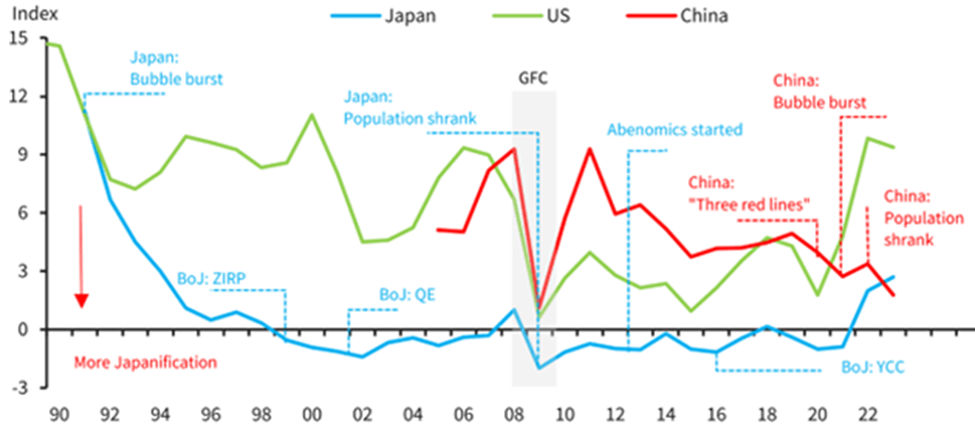

I saw an interesting Barclay’s study this week postulating that China is becoming more “Japanese” than Japan, economically speaking. Financial Times ran this excerpt (emphasis mine):

“The economic circumstances facing China have parallels with Japan’s experience after its asset bubble burst in the early 1990s. This created the term ‘Japanification,’ which is typically defined as a combination of slow growth, low inflation, and a low policy rate, accompanied by deteriorating demographic trends.

“To measure this phenomenon, a Japanese economist, Takatoshi Ito, introduced a Japanification Index, which measured the sum of the inflation rate, nominal policy rate, and GDP gap. To apply to China’s economy, we have adjusted this index, replacing the GDP gap with working-age population growth, as the estimation methods of GDP gaps differ across nations and working-age population is by far the most fundamental determinant for long-term growth. Our amended index shows that China’s economy has become more ‘Japanised’ than Japan’s recently, albeit marginally.

“This not a surprise to us. A demographic drag, the emergence and collapse of asset bubbles, debt overhang, zombie companies, deflationary pressures from excess capacity/high debt, and high youth unemployment, to name a few, are some of the notable similarities between the economies of China and Japan post their bubbles.”

Here is the index Barclay’s constructed. The lines represent each country’s inflation policy, interest rates, and working-age population. Japan began what we now call “Japanification” in the 1990s, decoupling from the US and then bouncing along near zero for about 20 years.

Source: Financial Times

China’s Japanification trend has been underway since the Great Financial Crisis years, and by this measure recently became worse than that of Japan itself.

Now, it is not necessarily the case that China will do what Japan did. You can ask my friend Louis Gave and he will make the counterfactual argument. And he has some good points. But the parallels are interesting. Japan became an export juggernaut; so did China. Japan had a real estate bubble; so did China. Japan’s bubble popped; so is China’s.

Tokyo’s solution was to keep interest rates near zero for decades and have the central bank buy every financial asset that wasn’t nailed down. It “worked” in the narrow sense Japan is still there. And while it has been at least 10 years since I’ve been to Japan, the times I’ve been there it certainly seemed relatively prosperous. It still is. But that doesn’t change the fact that Japan had almost no growth for 30 years and had to absorb an enormous amount of debt and stimulus. Whether it was a lasting solution, we don’t really know yet.

I’m trying to imagine what would happen if the PBOC adopted a Japan-like ZIRP. I don’t think it would go nearly as well. But they may not need to because China’s government has fewer pesky constraints, like voters.

That’s really the bigger issue. Maintaining the party’s power is always top priority in a Communist system. To some degree, this requires keeping the population happy and comfortable. Hungry people, even relatively uncomfortable people, are generally less cooperative (note sarcasm). But if push comes to shove, regime preservation comes first. Xi’s predecessors demonstrated that with the “Cultural Revolution” and later Tiananmen Square. Xi himself took a very firm hand with COVID and got away with it. So, in a financial crisis (real or contrived) I can imagine him getting tough in ways that wouldn’t work in Tokyo.

What is increasingly clear, though, is that the Beijing of today will seemingly not much longer tolerate even the mild, limited capitalism that produced today’s economy. It was never really sustainable in their political context. Capitalism requires failure, change, “creative destruction.” Leaders have to take their hands off the wheel and let bad things happen.

We have problems doing that even in the US. We keep bailing out failed banks, for example. What we should do is safeguard only the depositors while letting shareholders and unsecured creditors bear the losses. But that means people who made bad choices have to suffer. Even auto and steel companies.

Xi Jinping has no problem letting people suffer, but he won’t let market forces decide who it will be. What if the market decides China needs new leaders? That’s unacceptable. The government will always have at least a thumb on the scale… and maybe a foot.

Now, combine that with the growing geopolitical rivalry between China and the US. The two governments have actually done remarkably well at keeping trade open despite all the other differences. That’s good; our economies badly need each other, at least for now.

But look again at that population chart above. The US working-age population is projected to grow slightly while China’s drops hard. I know; AI is going to boost productivity. But a growing economy still needs human workers. At the end of the day, economic growth is the number of workers times productivity. I am a big believer that AI is going to change a lot of things. But then computers and the Internet changed a lot of things. And it seemed to show up everywhere except in the data.

China will be at a serious disadvantage on that front. Writing this letter brought to mind my friend Dr. Woody Brock’s research on the five stages of economic growth. The first three stages actually work well in a top-down managed economy. But then it falls apart in the last two stages as real economic growth requires bottom-up, market-oriented economics.

I thought also of my mentoring from Andy Marshall, perhaps the greatest geopolitical analyst in our country’s history. Andy was the Pentagon’s top “futurist analyst” for 52 years and under nine presidents. He taught me that over time, economic reality trumps political and government desires. In the mid-1970s he predicted the Soviet Union’s collapse as well as China’s rise. While skeptical of China’s long-term viability, he saw it as a serious national security threat.

The Soviet regime did indeed collapse, but Russia is still a viable country with a serious though greatly diminished military capability. I think China will have similar problems brought on by being a top-down economy. Beijing, while not a global power, will remain problematic for the rest of the world. But like Russia, they may not be investable.

Chinese leaders have a long history since Deng Xiaoping of pulling rabbits out of hats, so to speak. Maybe Xi or his successors will surprise the world again. But I wouldn’t want to be in their shoes.

Last week I said I didn’t have a trip scheduled in my future for the first time in memory. I knew that would change. I now have to be in Tulsa for Thanksgiving (the kids finally made a decision). I will stop in Dallas for some business meetings on the new longevity venture, which is coming together nicely. Then I have to be in Austin in early January and Newport Beach later that month. I have to get to New York at some point soon. This new business will probably make me travel more next year.

We talked about China and demographics above, but that it’s not just China. Longevity is going to become a big deal all over the world in the next 10 years because we are all getting older and want to live healthier longer. Moreover, countries will need their older citizens to stay productive. Fortunately, longevity technology is progressing quickly.

Literally as I was writing this, Patrick Cox’s first piece for Transformative Age hit my inbox. Patrick writes a monthly contribution to the service, focusing on bio enhancements or, more colloquially, “biohacking.” But instead of the typical goofy recommendations you see everywhere, Patrick writes about things supported by serious medical research. This week he talks about one of my personal favorites: hydrogen therapy. There are three ways to do this: one doesn’t work but the places will take your money. One is really expensive. One is cheap and seems quite effective. A lot of research says we need more hydrogen, as Patrick explains in detail. Basically, it helps get rid of free radicals.

I called Ed D’Agostino and said I want this letter to go out for free to everyone. You get Patrick at his best and you find a cheap, easy way to make yourself healthier. You can join Shane and me every morning. Click here to read the letter on hydrogen, with my compliments. Don’t skip to the end just for the recommendation. Read the entire piece and understand the science. There are scores of helpful things like this you can easily add to your life, and Patrick is the best in the world at writing about it.

With that, let’s hit the send button. Have a great week. And don’t forget to follow me on X. I am getting more active there and even controversial. I am enjoying myself.

Your dealing with his own longevity challenges analyst,

John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply