A challenge in writing a weekly letter like this is that the economy never stops. Important data keeps accumulating, whether I write about it or not.

A lot happened in the last four weeks: an FOMC meeting with major policy changes, a surprising jobs report, important shifts in the bond market and yield curve, hurricanes, China, some geopolitical events, and a political race, just to start. I haven’t mentioned them because I was on other, also important topics. Now it’s catch-up time.

One popular narrative right now says the economy is slowly returning to normal following COVID disruptions and then a severe inflation wave. That’s not entirely a fantasy; many long-term trends do appear to be resuming their pre-2020 paths. But it depends heavily on how you define “normal.” Some things change, others don’t. Normality is always a moving target.

Many analysts expect a recession by next year. Then again, those who have been forecasting the US economy to continue on its growth path have been right for some time. With the stock market making all-time highs this week, it does look more than merely Muddle Through.

The real distinction is between the economy we have today vs. the hypothetical, unknowable economy we would have if that virus had stayed where it came from and Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine. Today’s economy would probably look different. But that’s pure guesswork.

Can we still rely on rules forged in a world that no longer exists? Maybe. I’m more in the camp that we cannot—at least not without extraordinary caution. I believe with the government deficit and debt growing massively and the Fed’s aggressive policies, we have crossed a Rubicon, an “event horizon” where basing predictions on past data relationships is far more difficult. But since past data is all we have, forecasters still use it.

We do know one thing, however. The effects of 2020–2023—the pandemic, the Fed, the inflation, everything else—grow more distant with each passing day. The runway metaphor is overused but it fits: Planes can’t stay in the air forever. This one will land. The question is whether we passengers will feel a hard or soft landing.

The headlines in the media this morning are all about Hurricane Milton. I have so many friends I’m communicating with in Florida. It is a big deal. But I also have friends (and I assume readers) in Western North Carolina where the situation is even more dire. The death toll is already in the hundreds and will certainly grow. Locals tell me it could be well over a thousand. Infrastructure in many mountain communities will be down for months, if there is a community left. Whole towns have been wiped out. Talking to locals, it doesn’t sound like there was much of an evacuation effort, as unlike Florida, they had no experience with hurricanes.

I have a longtime friend, Tricia Zehr, who moved from California to Western North Carolina years ago. She has been my eyes and ears into the situation there.

It turns out there is a small church in the area called Anchor Baptist Church that has been doing relief work for over 35 years (since Hugo) for disasters all throughout the South. They have a professional staff with warehouses and facilities and a volunteer network plus a network of hundreds of churches they worked with in other disaster situations. Now, sadly, the disaster has come to their local area. Those churches they once helped are now reciprocating with supplies and volunteers.

Food for thousands of families is literally a problem. The church has become a central source for people to drop off supplies (near the local private airport) but is also then sending those supplies on to other churches throughout the area where local pastors and volunteers know the people in their local communities. They are connecting with these pastors and churches and sometimes flying them in with helicopters to find out who needs help when roads are not passable. They’re working with the local police and fire departments in the small towns to give them what they need, often with volunteer helicopters and planes, as the roads if they still exist are blocked. There are volunteers who literally use mules or horses to get to people back in the mountains. They coordinate volunteers to cut trees and clear housing and roads. I can’t even begin to describe the phone conversations about the amount of work they are doing.

They are going to be supplying food for months going into the winter, when tens of thousands of people will still be without homes. The Appalachians can get cold, and it is mid-October.

I could spend an entire letter writing about this, but let me ask my generous readers to make a donation to Anchor Baptist Relief. You can see some of the work they do here. 100% of your donations will go to relief supplies and food.

Back to the more mundane. The Federal Reserve started raising rates (way behind the curve) in March 2022 and stopped in July 2023. Then began the giant guessing game of when they would reduce rates. The answer turned out to be September 2024. We can debate whether the Fed waited too long or not long enough, but here we are.

While every cycle is different, this one seems particularly so. We are not following the “standard” sequence, which goes like this:

-

An overheated economy makes demand outstrip supply, causing price inflation.

-

Central banks tighten policy, discouraging credit-financed activity.

-

Employers reduce payrolls, leaving workers with less spending power.

-

Producers have to cut prices to maintain sales, ending the inflation.

-

Another growth phase begins and the cycle repeats.

The Fed’s power is mostly over short-term rates, primarily the overnight federal funds rate. The last year or so has been wonderful for savers, i.e., retirees or anyone holding a lot of cash. They’ve enjoyed nice, (almost) risk-free returns on money market funds, Treasury bills, etc.

Meanwhile, millions of homeowners who locked in low, fixed mortgage rates during the pandemic also have more spending power. This probably helped consumer confidence.

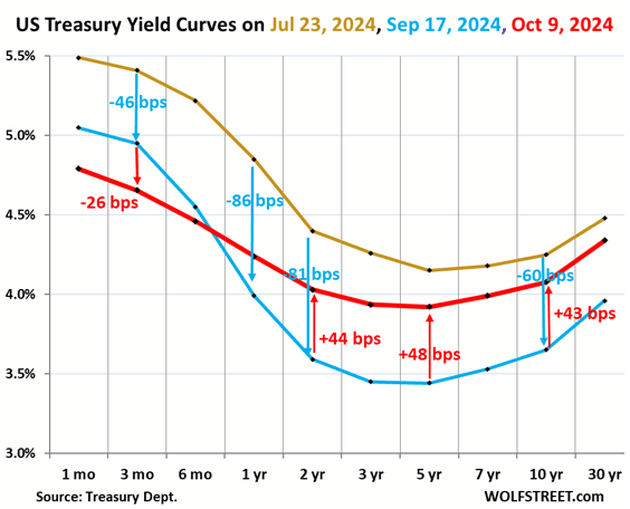

I suspect the Fed thinks its rate cuts at the short end would be accompanied by similar but slower declines at the long end, eventually restoring the yield curve to its normal shape. This would also bring down mortgage rates and reduce housing costs. If that was the theory, it’s not happening yet. Long-term Treasury and mortgage rates are actually up since the Fed began cutting.

In this case, the price inflation that began in 2021 wasn’t growth-induced. It was more about supply disruptions, though fiscal and monetary policy did spark some unwise speculation. Then a war caused Europe to reduce its dependence on Russian energy supplies, with global spillover effects.

Central bankers have few ways to solve those kinds of problems, but they had to “do something” about inflation. Higher rates didn’t slow consumer demand or raise unemployment, at least not initially and not much even now. GDP kept rising, rolling merrily along and surprisingly higher. The inflation rate came down in most categories, housing being the prime exception. Wages rose, even adjusting for inflation.

That sounds a lot like the “soft landing” most of us thought unlikely… but it’s not over yet. Much depends on how the economy responds to the new direction in interest rates. Here, we must talk about which rates are going in which directions.

Here’s the question: Who is going to be helped by modestly lower short-term rates? What activity are they going to stimulate that isn’t already happening? And who will be hurt?

Consider this chart from the invaluable Wolf Richter.

Source: Wolf Richter

The blue line is the yield curve on the day before the Fed’s cut. Notice how it compares to the red line 3+ weeks later. Rates at the short end fell, as expected. But debt maturities of a year and longer actually rose. Rates on the 10-year bond actually have risen 43 basis points. The difference is even greater since July (the gold line).

Mortgage rates (not shown here) generally take their cue from the 10-year Treasury yield, and indeed they rose, too. My friend Barry Habib of MBS Highway noted this isn’t unusual (even if it seems to be a surprise to some business media). Here’s Barry:

“This is not an unusual phenomenon—We have seen this happen in almost every rate cutting cycle except for 2019, and a lot of the reason why is investor psychology. Investors believe we have a greater chance of avoiding recession once the Fed starts cutting, which causes them to invest in the stock market at the expense of bonds. And the Fed cutting causes some to fear inflation rising once again, which causes bonds to temporarily sell off.

“But the Fed is cutting for a reason, and it’s because they are seeing the economy slow. And that helps the bond market and inflation come down. In each of the last instances where yields initially rose, they eventually fell much lower and we don’t believe this time will be any different.”

We will have to wait and see if Barry is right. I’m sure Jerome Powell hopes so; the Fed’s job will be a lot harder if long-term rates stay at these levels or rise further. It won’t be great for the federal debt problem, either.

Recession Brewing?

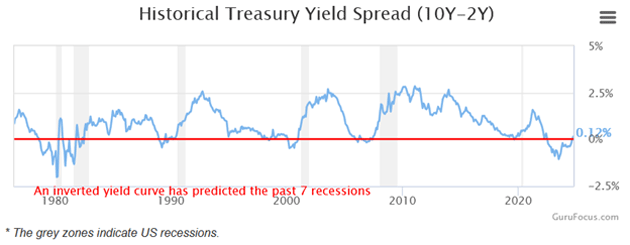

Speaking of the yield curve, we need to keep another historical pattern in mind. An inverted yield curve has long been one of the best recession indicators. In this case, the inversion happened in the summer of 2022. Why no recession yet? The indicator has been reliable but usually early. But two-plus years?

Back in May (see Liminal Space) I shared one of Dave Rosenberg’s SIC charts and talked about this. Quoting myself:

“… Notice how the yield curve inverts (i.e., drops below the zero line) months before recession, then rises and is back above zero before the recession arrives. Currently we are in the first part of that process: The yield curve, while still inverted, is headed back to its normal condition. If the pattern holds, it will cross back above zero and then another one of those gray recession bars will appear soon after.

“For this to happen, we need some combination of lower short-term rates and higher long-term rates. (That’s the definition of inversion; the 2-year Treasury yield is above the 10-year yield.) When that happens, you’ll probably see a bunch of analysts sound the all-clear. But in fact, we will be entering the danger zone.

“When could it happen? This week’s FOMC statement showed (if there was still any doubt) lower short-term rates are unlikely for several more months, at least.”

Again, that was from May 2024. Note the part I bolded where I said the line would cross above zero with recession likely soon after. That crossover just happened.

Source: GuruFocus

It’s hard to see, but that blue line just crossed back above zero, indicating the 10-year Treasury yield is slightly higher than the 2-year Treasury yield. The gap is small and has wavered a bit from day to day. But the inversion seems to be ending, which historically means recession should be brewing.

Is recession brewing? This is still unclear. Some data says yes, some no. Some analysts I deeply respect say no. The Fed seems most concerned about the unemployment rate, which has indeed risen quite a bit from its low last year. But that low was unusually low. The current level isn’t especially alarming; the concern is that it seems to be trending higher. But the strong September jobs report called that trend into question.

Other indicators—industrial activity, default rates, consumer spending, etc.—are inconclusive, too. And GDP shows nothing like recession; the latest data shows real GDP rose 3.0% in Q2 after a 1.6% Q1 reading.

The stock market isn’t acting like recession is near, either. No one is worried about earnings growth. Maybe they should be, but they’re not. The September inflation number was okay, but not as good as expected. Employment claims rose but the hurricanes could explain some of it.

And yet… if recession isn’t imminent, how do we explain the yield curve? I’m beginning to wonder what the years of extreme intervention since 2008 did to our indicators. Does the data still mean what we think it does? Maybe not. And that’s on top of questions on whether the data is even being measured correctly.

Everything I’ve learned and experienced in 50+ years of watching the economy tells me not to expect a soft landing. But maybe that’s because I’ve never actually seen one.

Broken Windows

If we are headed to recession, something will trigger it. What might that be?

Before this week, I had been thinking China was a strong candidate. I’ll save a deeper discussion for another letter, but the Chinese economy is in a rough stretch. Sheer size gives China global importance. The government is launching new stimulus programs so maybe all will be well. Or maybe not.

Closer to home, the devastation of hurricanes Helene and Milton is economically significant as well as heartbreaking. And no, it is not going to “stimulate the economy.” Frédéric Bastiat put that misnomer to rest back in 1850, but people continue to repeat it. Yes, a lot of money will be spent—and many jobs created—to repair and rebuild. Bastiat explained how this is only half the equation. You have to consider how all those resources would have been spent otherwise. Rebuilding houses that the hurricane destroyed isn’t growth. The economy gains nothing; it just recovers a lost asset, at significant cost.

Think also about the many thousands of victims, along with those who rushed to help them, who haven’t been doing their usual jobs. Some will be “unproductive” for months, in the normal sense of productive. Whatever output they would have generated isn’t going to happen now.

Yes, of course there will be some new activity. We’ll see increased demand for building materials, construction workers, and all the other things people lost and will want to replace. This will be inflationary, at least in those sectors. And it comes at a time when many kinds of skilled labor are already scarce and expensive.

Could these storms trigger recession—or rekindle inflation? If you read my Late Summer Sandpile letter, you know this is the wrong question. Sandpiles collapse on their own. The specific trigger is usually impossible to identify until it happens.

The economy has seen tremendous growth since the short (but deep) 2020 recession. We have built a very large sandpile in these years. The growth may continue but not forever. Let’s hope the collapse, whenever it comes, is a soft one.

A New Longevity Report

It was so nice to catch up with old friend Patrick Cox at my 75th birthday celebration. We talked at length about our new longevity and biotech newsletter project. Patrick believes we’re on the verge of dramatically extended healthy lifespans. I hope he’s right!

But as is often the case in an emerging field, there tends to be a lot of misinformation and hyperbole around the latest developments. To help our readers, I’ve asked Patrick to put together a special report on “Longevity Myths and Solutions.” He will be doing monthly updates on things you can do to improve your own health and lifespan. To get the free report and all the updates on this upcoming newsletter, sign up here.

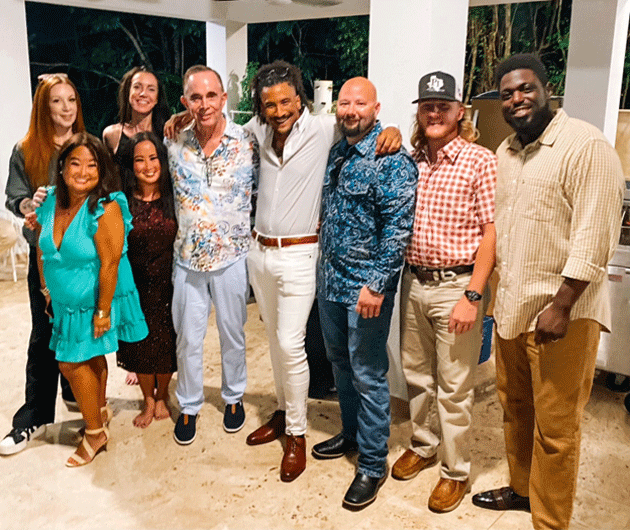

Birthdays and Hurricanes

It was an exhilarating four days, with all my children and grandchildren coming in Thursday, then more friends coming in Friday and Saturday. Two parties and lots of meetings. I will share two pictures below. The first is me and my 8 children. The second is my children, significant others, grandchildren, sisters and nieces and family. And yes, we are a tad more colorful than most families. But there has been a lot of love and joy over the years. I am still basking in the pleasure of those moments. Precious memories…

I am still pondering the telephone conversation that I had with the head of the crisis center at Anchor Baptist Church. He told me his family has been in the Appalachians for 200 years, and the town where he grew up simply no longer exists. A 30-foot wall of water took it out. Rescue operations are now finding far more victims than survivors. The only way to reach many of these communities is mule, horseback, or helicopter. They conveniently are only a short distance from the local airport, so they have become the de facto supply depot and distribution center. Fortunately, they have decades of experience.

One of the comments was that when they normally organize to go to a disaster relief area following a hurricane, from the time they could “mount up” to when they got there and began delivering services was typically five days. This time they saw the reverse of that problem. FEMA and government responders are now there but nobody had any conception that Western North Carolina could get hit like this. I have traveled around the back roads of that region and many of those small towns only had one road in/one road out. Picturesque and beautiful. Lots of tourism. And now some of them are simply gone.

I truly do hope you can join me in doing what little we can from our comfortable chairs. And with that, I will hit the send button and send a few prayers as well as dollars. And don’t forget to follow me on X!

Your thinking how quickly things can change analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Read the full article here

![Best 10mm Carbines [Tested] – Gun Digest Best 10mm Carbines [Tested] – Gun Digest](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/10mm-carbine-feature-kriss-vector.jpg)

Leave a Reply